Thank you for the kind introduction. While preparing these remarks, I learned that the Money Marketeers organization was founded by Dr. Marcus Nadler, a gifted educator who challenged market participants to deepen their understanding of the forces that move markets, and that it was born out of a popular lecture series he regularly held at NYU. This spirit of continual learning is a core value at the Federal Reserve, and that has been particularly important in recent years as the Fed has been operating in a new monetary policy implementation regime.1

I last had the pleasure of speaking about monetary policy implementation at this forum two years ago. At that time, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) had yet to make a decision on what the long run operating regime would look like. Substantial progress has been made since then. My intention tonight is to share some thoughts on what the FOMC’s recent decisions could mean for the manner in which the New York Fed’s Open Market Trading Desk (the Desk) implements policy. In particular, I would like to discuss the Federal Reserve’s ongoing process for learning about the banking system’s demand for reserves and money market dynamics more broadly. I will also outline how the Desk could supply reserves through open market operations as the Federal Reserve transitions from implementing policy in an ample-reserves regime driven by the asset side of the balance sheet to one driven by demand for liabilities.

I will bring an operational perspective to these topics, given my position as head of the Desk and Deputy Manager of the Federal Reserve System Open Market Account. I should also say now that the views I express tonight are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.

An Operational Framework for an Ample-Reserves Regime

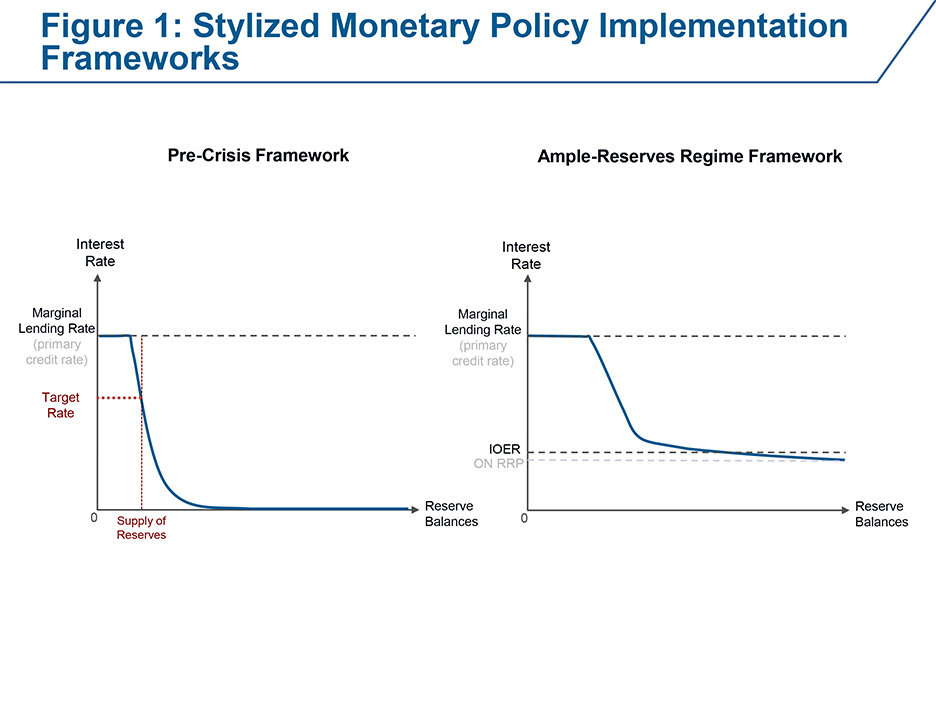

Let me begin by reviewing the FOMC’s recent decisions about the operating regime. In January, the FOMC communicated its intention to continue implementing policy in a regime in which an ample supply of reserves ensures that control over the federal funds rate and other short-term interest rates is exercised primarily through the Federal Reserve’s administered rates and in which the active management of the supply of reserves is not required.2 This type of regime is often referred to as a “floor system” because the administered rates—including IOER (the rate of interest paid on excess reserves) and the ON RRP rate (the offered rate at the overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility)—place a floor under the rates at which banks and other market participants will lend.3 I’ve illustrated this framework in the stylized graphs showing the relationship between the interest rate and banks’ demand for reserves in Figure 1. Before the crisis, the Desk operated along the steep part of the demand curve to achieve its directive from the FOMC, whereas in an ample-reserves regime, like the one we’ve used in recent years, we operate along the flatter part of the curve.4

Over the past decade, the Federal Reserve has learned a great deal about operating in the current regime, and during recent deliberations about the long-run implementation framework the FOMC highlighted several key benefits of the current regime as supporting its decision.5

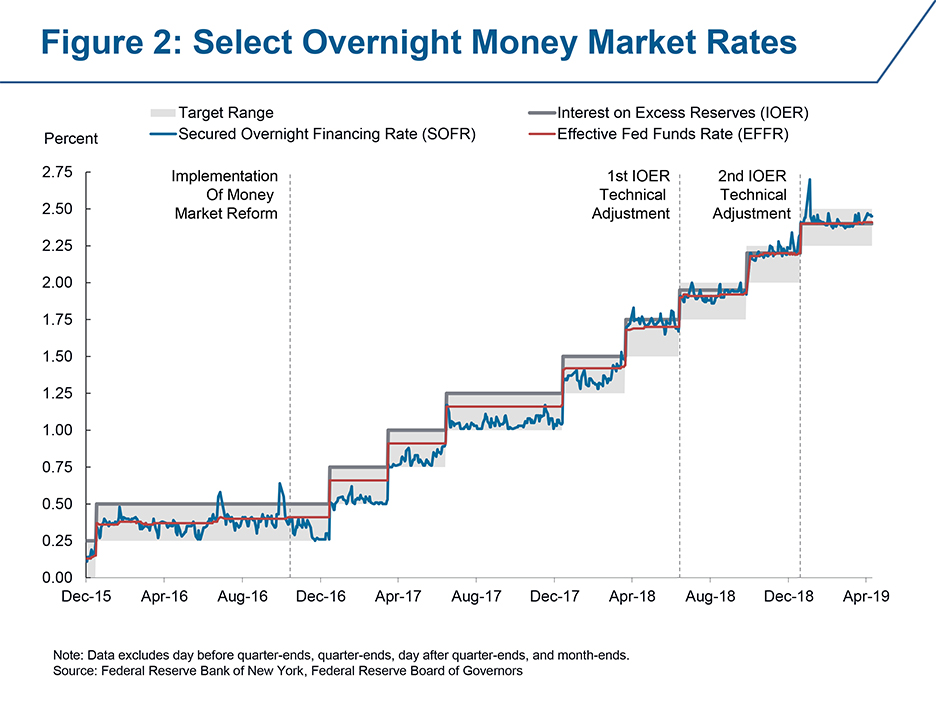

First, the ample-reserves regime has been very effective at controlling short-term interest rates because the Federal Reserve’s administered rates provide strong incentives in money markets. As shown in Figure 2, overnight interest rates moved in line with changes in these administered rates, even as the FOMC lifted rates from near zero in late 2015 to over 2 percent more recently. During this same period, there were sweeping changes in banks’ liquidity management practices and in money market fund regulation that transformed the structure of money markets, and the floor system proved resilient to those changes.6 Looking forward, this regime should provide stable interest rate control if unexpected situations arise in which large amounts of liquidity need to be added to relieve stress in the financial system or large-scale asset purchases are needed to provide macroeconomic stimulus because short-term rates are at their effective lower bound.7

Second, from an operational perspective, an ample-reserves regime achieves this effectiveness in a simple and efficient manner. For example, it reduces the need for active management of reserve supply because shocks to the supply of or demand for reserves can be absorbed without the need for sizable daily interventions by the central bank. In the U.S., the ability to accommodate variability in non-reserve liabilities is particularly important because those liabilities—such as the Treasury General Account (TGA), Foreign Repo Pool, and balances held by Designated Financial Market Utilities—provide benefits for the economy and the global financial system.8

Although reserves will continue to be ample going forward, the level will be significantly lower than has prevailed in recent years. In March, the FOMC issued an updated “Balance Sheet Normalization Principles and Plans” in which it stated that the longer-run level of reserves will be a level consistent with “efficient and effective” implementation of monetary policy.9 To support a smooth transition to the longer-run level of reserves, the FOMC also stated that the reduction in the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings will slow this spring and then stop in September. When balance sheet runoff stops in September, the FOMC expects the level of reserves to be somewhat higher than necessary for efficient and effective monetary policy implementation. If so, the total balance sheet will be held constant for a time, and trend increases in non-reserve liabilities, such as those shown in Figure 3, will gradually reduce the average level of reserves until it reaches a level consistent with efficient and effective implementation of monetary policy.

As Chair Powell noted in his January press conference, the level of reserves consistent with efficient and effective implementation of monetary policy will be principally determined by financial institutions’ demand for reserves, and an additional buffer so that interest rate control continues to be exercised through administered rates.10 The stylized framework I showed earlier in Figure 1 illustrates that banks demand different levels of reserves depending on the prevailing levels of interest rates. However, for purposes of the discussion today, I will define the banking system’s demand for reserves as a level that is just to the right of the steeper portion of the demand curve, representing the lowest quantity of reserves that banks demand in aggregate at rates near IOER. This corresponds to the minimum level of reserves needed to continue operating in a floor system, and supplying reserves at or above this level would be consistent with a floor system.

In practice, assessing banks’ demand for reserves will be a continual process because the factors determining that demand are complex and may change over time. Federal Reserve staff survey banks, analyze vast amounts of data, and gather intelligence across the market to better understand this demand. Slowing the runoff in securities holdings this spring and stopping in September will reduce the pace of reserve decline, allowing this detailed assessment to adapt appropriately as reserves decline to levels that were last seen almost a decade ago. The behavior of money markets with this lower—albeit still ample—level of reserves will feed back into the Desk’s thinking about the design of operations. And being operationally flexible will allow the Desk to adapt to changing economic and market conditions, as well as to the FOMC’s assessment of the appropriate level of reserves consistent with efficient and effective implementation.

The Banking System’s Demand for Reserves in an Ample-Reserves Regime

Let me take a step back and provide some observations on the banking system’s demand for reserves. Banks engage in a variety of activities that create uncertainty about their liquidity positions. These uncertainties include a risk that depositors will want their money back sooner than expected. To manage this liquidity risk, banks need access to cash, which can come from several sources, including reserves already held at the Federal Reserve, money borrowed either in the private market or from the Federal Reserve’s lending facilities, or proceeds from asset sales or maturities.

Reserves are the most reliable and safest source of liquidity because they are immediately available for payments and do not have a changing market value. Nevertheless, before the crisis, banks typically tried to minimize reserve balances because reserves earned zero interest, whereas other highly liquid assets, such as Treasury bills, earned a sizable positive yield. Given this high opportunity cost, demand for reserves was relatively close to reserve balance requirements prior to the crisis.11

Today, reserves are less expensive to hold than they were before the crisis because the Federal Reserve now pays IOER, which is the principal tool used to control short-term interest rates.12 However, demand for reserves has also shifted in other important ways. In particular, there are new factors driving reserve demand, and that demand is, and will likely continue to be, much higher than it was before the crisis. To start, the crisis appropriately changed attitudes toward risk and increased focus on managing liquidity risk. The subsequent creation of a liquidity regulatory framework for larger banks reinforced the benefits of holding unencumbered liquid assets for both domestic and foreign banks. While these liquidity regulations do not themselves impose any specific requirements to hold central bank reserves, many banks now use internal models that also estimate the very short-term liquidity they need to hold in order to be prepared for a stress scenario.13 These models make assumptions about a bank’s reduced access to funding and ability to sell securities during earlier stages of a stressed period. The bank may therefore decide to hold a portion of its liquidity buffer as reserves on an ongoing basis as a precautionary measure. Through our outreach to banks, we also hear that some are more reluctant to borrow from the Federal Reserve than they were prior to the financial crisis. For some banks, this reluctance increases the precautionary demand for reserves to meet large intraday payment obligations and manage unexpected volatility in deposits.

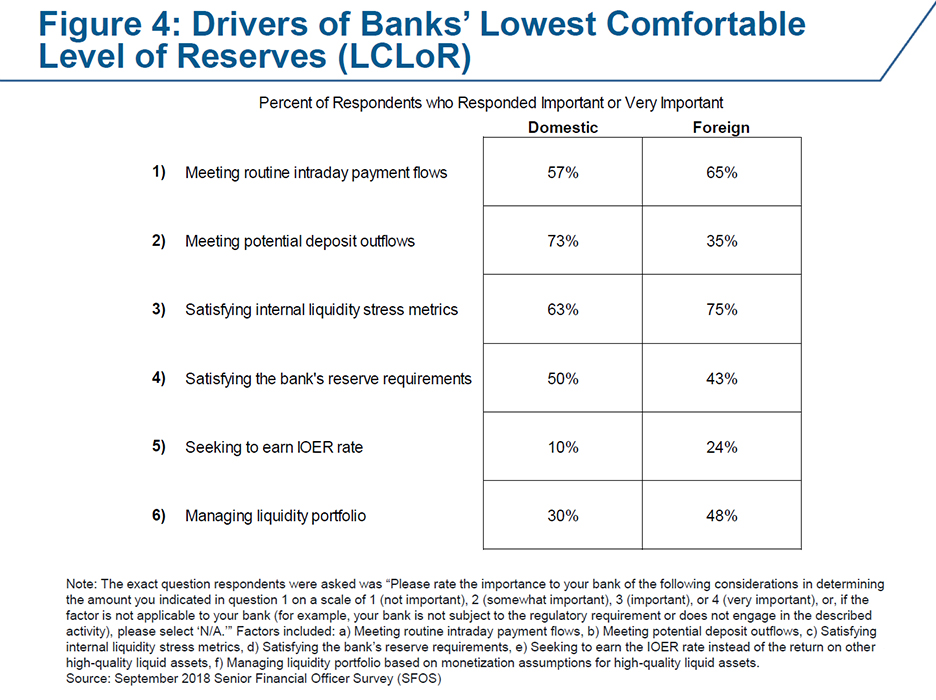

To get a more systematic reading of the factors driving reserve demand as well as the size of this demand, the Federal Reserve conducted a Senior Financial Officer Survey (SFOS) in September 2018 and again this February.14 The respondents to the September 2018 survey held two thirds of all reserves and about 60 percent of assets in the banking system, and they encompassed a diverse set of business models, including foreign banks and domestic banks of different sizes.

The survey results revealed that a number of important sources of reserve demand are present. As shown in Figure 4, which presents September 2018 survey responses, the majority of both domestic and foreign banks cited internal liquidity stress tests and meeting intraday payment flows as important or very important drivers of reserve demand. In addition, meeting potential deposit outflows specifically was important or very important for almost three quarters of domestic banks, compared to around a third of foreign banks.15 In addition, it is worth highlighting the considerable variation in survey responses, which reinforces my earlier point that the pre-crisis framework in which all banks had similar reserve management strategies no longer applies. The diversity of drivers also highlights how demand for reserves could change if banks move from one strategy to another or refine an existing one over time.

The survey can also be used as an input for quantifying the banking system’s demand for reserves. The surveys asked each bank to report the level of reserves it would hold (at the prevailing constellation of rates) before taking active steps to maintain or increase its reserve balances.16 This lowest comfortable level of reserves, or “LCLoR,” corresponds, conceptually, to the part of a bank’s demand curve where the slope could start to steepen. In the September 2018 survey, total LCLoR of all the respondents was $617 billion, and extrapolating the survey responses to the banking system as a whole resulted in estimates of U.S. banking system demand for reserves ranging from $800 billion to $900 billion.17 When we surveyed banks again in February, those results yielded estimates in the same range. Figure 5 shows total LCLoRs for foreign respondents and domestic respondents, and the extrapolated demand for the rest of the banking system. As you can see, each group has considerable demand for reserves, although this demand is still well below current reserve levels and far below the peak reserve levels reached in 2014.

To connect this back to the stylized framework, in a world with perfect information and no financial market frictions, an estimate of aggregate reserve demand derived from summing and scaling the reported demand of individual institutions might correspond to a level just to the right of the steeper portion of the demand curve. However, there are reasons why the amount of reserves a central bank needs to supply to remain in a floor system could deviate from such an estimate. First, an estimate of demand for reserves is simply an estimate; the true amount could be higher or lower. Second, an individual bank’s demand curve could change over time, both for reasons specific to the bank and because of changes in the economic or market environment. Third, the banking system’s demand for reserves could be higher than the sum of each bank’s individual demand if reserves are not distributed efficiently. This scenario could occur if there are financial market frictions to redistributing reserves that result in some banks persistently holding a surplus of reserves above their LCLoR. For example, banks now suggest that they face higher balance sheet costs to lend in federal funds, making it possible that this market would not be as efficient at redistributing reserves late in the day as it was prior to the crisis.18

In practice, assessing the lowest level of reserves necessary to remain on the flat, or flatter, part of the demand curve will entail not only periodically conducting the SFOS in collaboration with the Board of Governors, but also broader monitoring and analytical efforts in order to continuously inform our assessment of the demand for reserves and reserve conditions. The Desk’s current assessment is that reserves remain ample overall. Transacted rates in the federal funds market are relatively stable, and the vast majority of trades are within the target range. Additional monitoring of bank microdata also suggests that reserves are well supplied.19

Let me walk through some observations based on the Desk’s ongoing monitoring and analysis. Though rates transacted in the federal funds market are relatively stable, the EFFR has risen one basis point relative to IOER in recent weeks and is now above IOER. Since mid-March, overnight repo rates have generally traded above federal funds rates, providing an attractive investment opportunity for the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) that invest a portion of their liquidity portfolios in both markets. As the dominant lenders in the federal funds market, FHLBs may have been able to negotiate higher overnight lending rates with banks that regularly use federal funds to fund non-reserve assets or meet payments, and on occasion with banks that borrow to improve their Liquidity Coverage Ratios (LCR) by borrowing from government sponsored enterprises.20

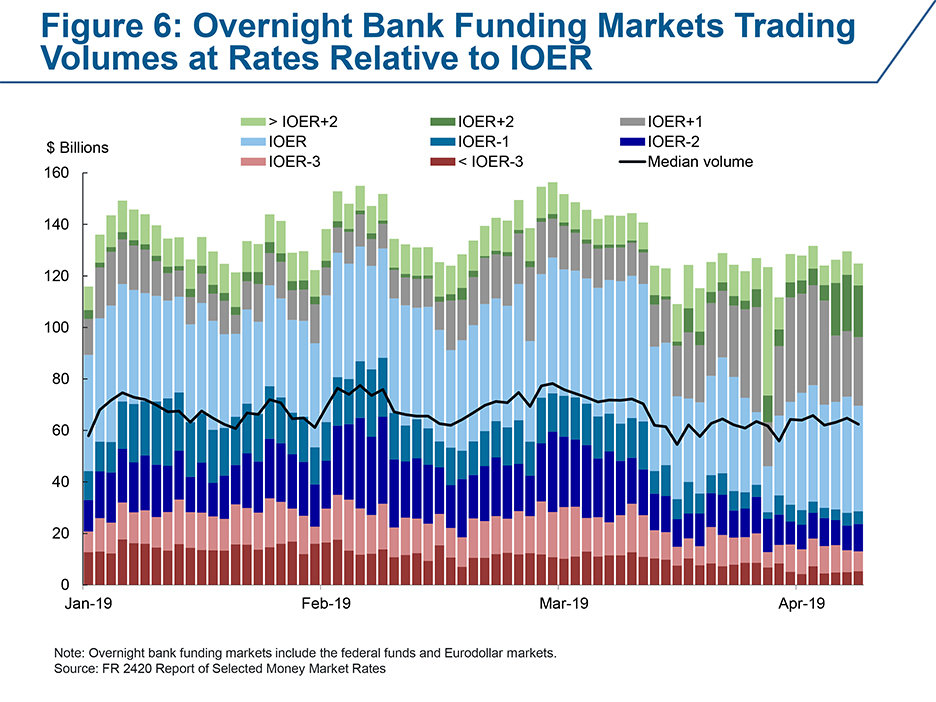

In line with a slightly higher EFFR, the overall share of above-IOER borrowing in markets underlying the overnight bank funding rate has been growing somewhat, as shown in Figure 6, although a large majority of activity is still transacted within a couple of basis points of IOER. As long as these rates remain relatively stable and at modest spreads above IOER, we don't see this as indicating that reserves are not well supplied.

Indeed, an examination of daily reserve levels of individual banks shows that currently most banks remain well above their reported LCLoRs, suggesting that reserves remain ample. In fact, some banks with surplus reserves have been redistributing these reserves by shifting the composition of their HQLA (high quality liquid assets) by lending in repo markets when rates are attractive, suggesting secured markets are providing a means to redistribute reserves.

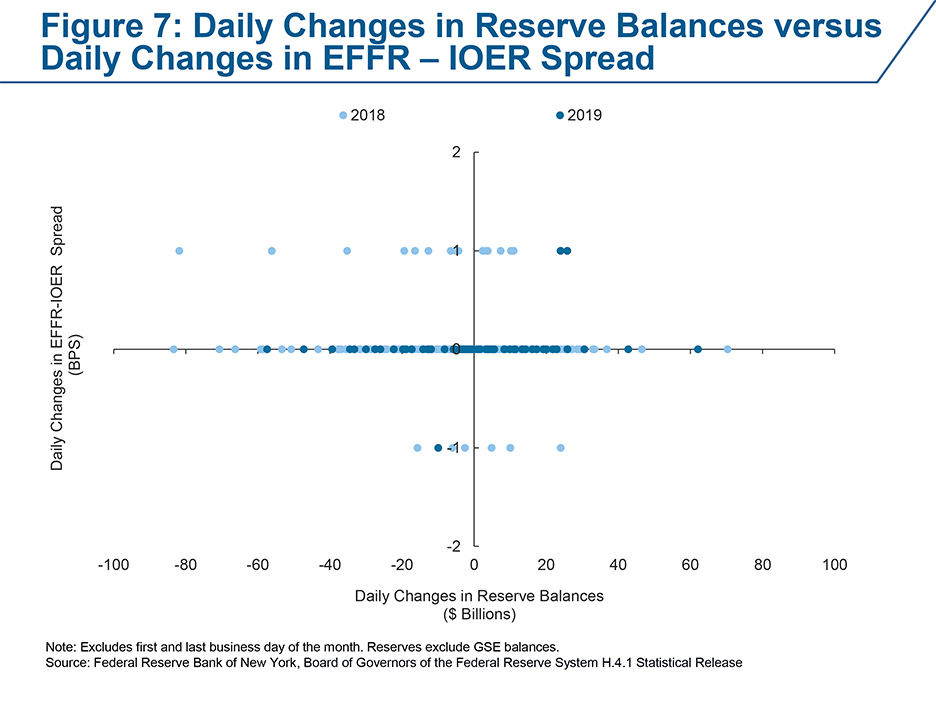

If competition for reserves were to increase, we might expect to see a more meaningful day-to-day relationship between changes in the level of reserves and overnight rates. Figure 7 shows a scatterplot of daily changes in reserve balances against daily changes in the spread between EFFR and the IOER rate. There continues to be no discernable relationship.

In sum, a wide range of information contributes to the Federal Reserve’s assessment of reserve demand and reserve conditions. The Desk’s current view is that reserves remain ample and well above the level the banking system demands at rates near IOER at this time. Our assessment of reserve demand is likely to change over time as we continue learning, and could move higher or lower based on new information from analysis of data, surveys, and outreach.

Supplying Reserves in an Ample-Reserves Regime

I will now look ahead and turn to how the Desk could supply reserves through open market operations to maintain an ample-reserves regime. After balance sheet runoff ends in September, the average level of reserves will decline more slowly, although there will be some meaningful transitory swings in reserve levels because of normal variability in the Federal Reserve’s other liabilities. As the level of reserves declines, the Desk will monitor medium-term forecasts of reserves and other indicators of reserve conditions. At some point, the FOMC will decide that the system has reached a level of reserves consistent with efficient and effective implementation.

Once this determination has been made by the FOMC, the Desk will need to conduct outright purchases of Treasury securities to supply reserves in order to offset the general decline in reserves from trend growth in non-reserve liabilities and ensure that reserves remain ample.21 In this regard, these purchases will have the same purpose as they did prior to the financial crisis—expanding the size of the SOMA portfolio to accommodate growth in currency and other liabilities. However, the size of these purchases will likely be larger in nominal terms because the growth of non-reserve liabilities is larger. For example, in 2018, currency increased by almost $100 billion, as shown back in Figure 3, compared to average increases of $40 billion a year in the early 2000s before the crisis.

These purchases could also be structured in size and timing to supply a sufficient amount of reserves so that normal variability in non-reserve liabilities would not require predictable repo market operations to offset the corresponding reserve level changes.22 The size of this “buffer” of reserves would depend on the Desk’s forward-looking assessment of the expected volatility in non-reserve liabilities. A buffer of reserves executed through Treasury purchases would diminish the need for the Desk to conduct frequent, sizable repo operations, which might be difficult to implement given reduced elasticity of primary dealer balance sheets for tri-party repo in the post-crisis era.2 Nonetheless, even with this type of approach to managing a buffer, there might be some occasions in which unanticipated changes in reserve conditions would still require the Desk to conduct repo operations to maintain reserve levels or keep the effective federal funds rate in the target range consistent with the directive from the FOMC.

Let me make the discussion of the buffer more concrete by focusing on the TGA. The TGA is an account the Federal Reserve provides to the U.S. Treasury which, similar to a checking account, allows Treasury to deposit or withdraw cash every day. When Treasury takes in cash (for example, tax receipts), money is withdrawn from a private bank account that in turn comes out of that bank’s reserves holdings. So, when the TGA increases—and assuming there are no other changes on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet—this corresponds to a decrease in the level of reserves. Figure 8 shows a scatterplot of weekly changes in the TGA against weekly changes in reserves over the past two years. There have been times when the TGA has increased by around $100 billion over the course of a week and there has been a similarly large decline in reserves.24 Figure 9 shows the distribution of weekly changes across all non-reserve liabilities. These changes have grown since the crisis and last year were as large as $100 billion. Managing a buffer of reserves above the banking system’s demand for reserves would help absorb these fluctuations in non-reserve liabilities.

As the level of reserves falls, the Federal Reserve will continue to learn and enhance its thinking about an efficient approach to open market operations that could incorporate both the trend growth and transitory volatility in non-reserve liabilities to maintain the excellent interest rate control experienced with higher levels of reserves.

While my discussion tonight has focused on the structure of open market operations from the perspective of supplying sufficient reserves in an ample-reserves regime, the FOMC also announced in its March Principles and Plans that the Desk will be conducting Treasury purchases in the secondary market to reinvest mortgage-backed securities (MBS) principal payments starting in October (subject to a maximum of $20 billion per month). The size of these purchases will vary over time based upon MBS prepayments. Of course, these purchases will be altering the composition but not the overall size of the System Open Market Account portfolio and Federal Reserve balance sheet. At least initially, the FOMC will direct the Desk to conduct these MBS reinvestment purchases across a range of Treasury maturities to roughly match the maturity composition of securities outstanding. The Desk will provide more details on these operations in May.25

Closing Thoughts on Continually Learning and Remaining Flexible

In conclusion, the FOMC made an important decision in January to continue to implement policy in an ample-reserves regime. Whereas the size of the balance sheet and the level of reserves have, for many years, been driven by Federal Reserve asset policies, at some point they will be determined by the demand for Federal Reserve liabilities, taking into account both the banking system’s demand for reserves and volatility in non-reserve liabilities.

Through outreach, surveys, and regular monitoring we have increased our understanding of the banking system’s demand for reserves. This learning is ongoing, and we expect the factors driving reserve demand to evolve over time. The Desk’s current assessment is that reserves are ample, and we will continue to monitor conditions closely to further enhance our understanding of reserve conditions and reserve demand.26

Looking ahead, after balance sheet runoff ends in September, average reserve levels will likely continue to gradually decline. When the FOMC judges that reserves have reached a level consistent with efficient and effective implementation, the Desk will begin to execute gradual and mechanical purchases of Treasury securities in order to ensure that reserves remain ample. The size of these purchases will need to be larger than similar pre-crisis operations simply because trend growth in non-reserve liabilities is larger in nominal terms, and because proceeds from maturing MBS also will be reinvested.

These are unprecedented times, so active learning and maintaining operational flexibility will continue to be core principles that guide the implementation of monetary policy. The ample-reserves operating framework I have described today has auxiliary mechanisms, such as an ongoing process for assessing reserve demand, that allow for flexibility and adaptation for continued successful control of interest rates going forward.

Thank you. I would be happy to take a few questions.