-

- About the New York Fed

- What We Do

- Communities We Serve

-

More About Us

-

At the New York Fed, our mission is to make the U.S. economy stronger and the financial system more stable for all segments of society. We do this by executing monetary policy, providing financial services, supervising banks and conducting research and providing expertise on issues that impact the nation and communities we serve.

The Teller Window is a publication featuring expert knowledge and insight from the New York Fed, including thoughts and perspectives from senior leaders.

Do you have a request for information and records? Learn how to submit it.

Learn about the history of the New York Fed and central banking in the United States through articles, speeches, photos and video.

-

- Markets & Policy Implementation

-

- Reference Rates

- Effective Federal Funds Rate

- Overnight Bank Funding Rate

- Secured Overnight Financing Rate

- SOFR Averages & Index

- Broad General Collateral Rate

- Tri-Party General Collateral Rate

- Desk Operations

- Treasury Securities

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Repos

- Reverse Repos

- Securities Lending

- Central Bank Liquidity Swaps

- System Open Market Account Holdings

- Primary Dealer Statistics

- Historical Transaction Data

-

- Monetary Policy Implementation

- Treasury Securities

- Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Agency Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities

- Agency Debt Securities

- Repos & Reverse Repos

- Securities Lending

- Discount Window

- Treasury Debt Auctions & Buybacks

as Fiscal Agent - INTERNATIONAL MARKET OPERATIONS

- Foreign Exchange

- Foreign Reserves Management

- Central Bank Swap Arrangements

- ACROSS MARKETS

-

- Economic Research

- U.S. Economy

- Consumer Expectations & Behavior

- Growth & Inflation

- Economic Heterogeneity Indicators (EHIs)

- Multivariate Core Trend Inflation

- New York Fed DSGE Model

- New York Fed Staff Nowcast

- R-star: Natural Rate of Interest

- Labor Market

- Financial Stability

- Corporate Bond Market Distress Index

- Losses from Natural Disasters

- Outlook-at-Risk

- Treasury Term Premia

- Yield Curve as a Leading Indicator

- Banking

- RESEARCHERS

-

- Financial Institution Supervision

- Bank Applications

-

As part of our core mission, we supervise and regulate financial institutions in the Second District. Our primary objective is to maintain a safe and competitive U.S. and global banking system.

The Governance & Culture Reform hub is designed to foster discussion about corporate governance and the reform of culture and behavior in the financial services industry.

Need to file a report with the New York Fed? Here are all of the forms, instructions and other information related to regulatory and statistical reporting in one spot.

The New York Fed works to protect consumers as well as provides information and resources on how to avoid and report specific scams.

-

- Financial Services & Infrastructure

-

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York works to promote sound and well-functioning financial systems and markets through its provision of industry and payment services, advancement of infrastructure reform in key markets and training and educational support to international institutions.

The New York Innovation Center bridges the worlds of finance, technology, and innovation and generates insights into high-value central bank-related opportunities.

The growing role of nonbank financial institutions, or NBFIs, in U.S. financial markets is a transformational trend with implications for monetary policy and financial stability.

The New York Fed offers the Central Banking Seminar and several specialized courses for central bankers and financial supervisors.

-

- Community Development & Education

-

- Staff

-

Fed System Initiatives

- Other Community Development Work

- Calendar

-

Outlook-at-Risk provides estimates of the conditional distribution of the future evolution of these key economic variables based on the relationship with the level of financial conditions.

New estimates of the conditional and unconditional distributions are published at or shortly after 10 a.m. on the third Wednesday of each month.

How to cite this report:

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Outlook-at-Risk, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/policy/outlook-at-risk.

Related reading:

Disclaimer

Outlook-at-Risk is not an official estimate of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, its President, the Federal Reserve System, or the Federal Open Market Committee.

Outlook-at-Risk provides an objective way of quantifying the risks around future real GDP growth, the unemployment rate, and inflation by capturing how such risks evolve as financial conditions ease or tighten.

Adrian, Boyarchenko, and Giannone (2019) showed that risks to real activity evolve as economy-wide financial conditions change, with the probability of a decline in real activity rising as financial conditions tighten. This negative relationship between real activity and financial conditions is strongest when the chances of a pronounced decline in real activity are high—in other words, when the economy is “at risk.” Following a similar approach, Adams, Adrian, Boyarchenko, and Giannone (2021) showed that the risk that the unemployment rate rises in the future or that the rate of inflation rises or falls from its current level is also presaged by tight financial conditions.

In the spirit of this work, Outlook-at-Risk follows a similar methodological approach and estimates the conditional distribution of future real gross domestic product (GDP) growth, the unemployment rate, and consumer price index (CPI) inflation based on contemporaneous financial conditions for each month since January 1989.

The world is uncertain and so quantitative approaches to measuring the changing risks to the outlook are a valuable tool. Although there is extensive work and numerous existing resources available that endeavor to characterize the likely path of the economy, relatively little work has studied the entire distribution of future economic outcomes. Outlook-at-Risk provides a useful complement focusing on other aspects of the distribution, such as economic outcomes that are less likely (often referred to as the “tails” of a distribution).

There are two key ingredients to the approach. First, it uses near-term forecasts (one quarter to four quarters ahead) for the economic variables of interest: real GDP growth, the unemployment rate, and CPI inflation. Monthly forecasts are obtained from the Blue Chip Economic Indicators Survey (BCEI). These data are proprietary but are available for purchase. For the realized variables, it uses the third release of real output growth available from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Real-Time Data (available here) corresponding to real gross national product (GNP) growth prior to 1992 and real GDP growth thereafter. It also uses the civilian unemployment rate (U-3 unemployment rate) and the consumer price index for all urban consumers, both available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Second, it uses a measure of overall U.S. financial conditions, the Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress (CISS), which is produced by the European Central Bank and is available here. Importantly, when each distribution is estimated, only information that would have been available at the time is used. This avoids “look ahead” bias, which could lead to misleading inferences.

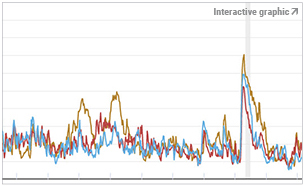

The main tabs of the product present the current estimates of the conditional and unconditional distributions for each of the three economic variables. The tabs also present the time series of the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percent quantiles (or percentiles). A percentile provides information about how likely events are to occur above or below a certain value. For example, the 10th percentile of the distribution of future real GDP growth is the rate of growth such that there is an estimated 10 percent probability of future growth being less than or equal to it. To give a specific example, in the second chart in this blog post, the shaded area represents the probability that average real GDP growth over the next four quarters is below -0.1 percent, which, in November 2019, was assessed to be 10 percent. Thus, -0.1 percent is the 10th percent quantile (or percentile) of the conditional distribution of average real GDP growth over the following four quarters. A more negative (lower) estimate of the 10th percentile indicates greater downside risks to real GDP growth.

Because Outlook-at-Risk estimates the entire distribution of future outcomes, it facilitates the study of a number of important features about the outlook. For example, the most likely value is referred to as the mode of the distribution and it is the value on the x-axis corresponding to the highest point in the distribution. As another example, the difference between a high and low percentile, such as the difference between the 90th and 10th percentile, is a measure of uncertainty, with a longer gap indicating that a wider range of possible future values are likely. Measures such as this are appropriate for CPI inflation and indicate the risks of a wider range of future inflation occurring. For real GDP growth, where one might be concerned about reduced activity, percentiles in the left tail (such as the 10th percentile) provide information about the risks of future anemic growth or contractions. Similarly, for the unemployment rate, where one might be concerned about deterioration in the labor market, percentiles in the right tail (such as the 90th percentile) provide information about the risks of such a slowdown.

To obtain the estimated distributions, Outlook-at-Risk relies on so-called quantile regressions, which allow the assessment of how certain features of the distribution of future macroeconomic variables (in this case, particular quantiles) relate to the level of financial conditions. Suppose one is interested in the 25th percent quantile of future real GDP growth. Quantile regressions allow for the estimation of how the 25th percent quantile of the desired distribution co-moves with financial conditions. Repeating this exercise for different quantile choices begins to be informative about the overall shape of the conditional distribution of real GDP growth. To estimate the full distribution, Outlook-at-Risk then chooses the best fit from a large family of candidate distributions to the predicted 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percent quantiles.

For real GDP growth and CPI inflation, Outlook-at-Risk considers risks around the average quarterly growth rate over the next four quarters; however, for the unemployment rate it considers risks around the quarterly average in four quarters’ time. Why the difference? The time series of real GDP growth and CPI inflation are subject to considerable quarter-to-quarter transitory variability that can be “smoothed out” by taking averages over multiple quarters. In contrast, the unemployment rate has little to no transitory variability, and so taking averages over multiple quarters is unnecessary.

Selected percentiles (P10, P25, P75, P90) of the forecast error distribution for each series are available for download.