Thank you for the invitation to speak at today’s workshop discussing asset purchases by central banks. We all have the opportunity to learn from different central banks’ experiences in recent years.1

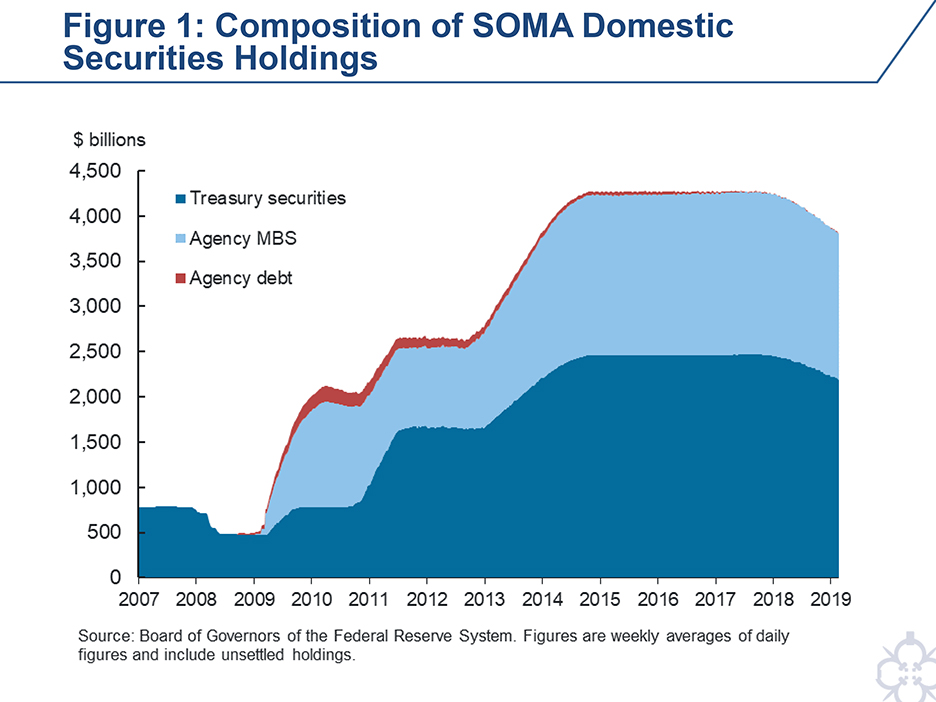

Between the middle of 2008 and late 2014 the Federal Reserve expanded the size of its balance sheet from around $900 billion to about $4.5 trillion. During that time, the Fed conducted three large-scale asset purchase (LSAP) programs, two of which specifically targeted agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and programs to reinvest principal paydowns. These programs altered the composition of the System Open Market Account’s (SOMA) domestic securities portfolio from one consisting entirely of U.S. Treasury securities to one including approximately 40 percent agency MBS (Figure 1).2 Overall, the Federal Reserve purchased over $4 trillion in agency MBS—fairly evenly split between LSAP and reinvestment purchases—with holdings peaking just below $1.8 trillion.3 I will focus my remarks today on the Federal Reserve’s experience with these purchases of agency MBS.

Before I continue, I will note that the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.

LSAP Transmission Channels

There are many broad transmission channels through which LSAPs can provide additional monetary accommodation:

- Increasing the monetary base and central bank liabilities—viewed as the main quantitative easing (QE) channel prior to 20084

- Reinforcing that interest rates will remain low—the signaling channel5

- Changing the quantity and mix of financial assets held by the private sector—the portfolio balance channel

- Taking interest rate risk out of the private sector—the duration channel

- Improving market function—the market function channel

- Taking credit risk out of the private sector—the credit channel

- Taking prepayment risk out of the private sector—the prepayment channel

The purchases of different types of assets will work through these channels in varying degrees. For example, sovereign assets will generally work primarily through the first five channels, while certain non-sovereign assets would also work through the credit or prepayment channels.6 Overall, the purchase of non-sovereign assets can be helpful by providing additional channels for monetary accommodation to be realized. In addition, it can allow central banks to overcome functional limitations that could exist if they were restricted to LSAPs in only one market—although the Federal Reserve is lucky to have very deep and liquid U.S. Treasury and agency MBS markets.

Purchases of Agency MBS

For an asset class to be valuable as part of an asset purchase program, it must be deep enough to allow a meaningful amount of purchases and liquid enough to allow transactions to be conducted at a fast pace without causing a material deterioration in market functioning. With over $6.3 trillion outstanding and an estimated average daily trading volume of over $200 billion in 2018, agency MBS meet these criteria.7

The depth and liquidity of the agency MBS market are assisted by the existence of the to-be-announced (TBA) MBS trading convention. This structure provides investors with the ability to trade a wide range of MBS with a handful of similar characteristics without requiring them to analyze the underlying details of each individual mortgage security.8 It transforms a market of hundreds of thousands of individual mortgage securities into a limited number of homogenous TBA contracts.9 In addition, TBA market trading conventions provide mechanisms for adjusting previously agreed-on settlement terms. Dollar rolls can be used to extend the settlement date by one month, and coupon swaps can be used to switch the specific TBA contract being purchased for one with a different coupon rate. These trading tools have been used to facilitate efficient settlement and can alleviate market stress.10

However, adding a new asset class can also bring new challenges, requiring a central bank to learn more about an asset class and to build or refine the internal systems needed to operate in that market.11 Furthermore, the clearing, settlement and custody of agency MBS require unique attention.12 Finally, there may be political economy perspectives to consider when buying assets other than sovereign government debt, such as benefiting specific economic sectors or private entities. Many might argue that the main issuers in agency MBS gained private benefits at the expense of the taxpayers in the period prior to the financial crisis.13 An aversion to perceptions that agency MBS allocate credit across sectors of the economy could be a consideration in any future decision to undertake purchases.

Lessons Learned (and To Be Learned) about MBS Purchases

Since 2008, the Fed purchased agency MBS through two of its LSAP programs and through its reinvestment program.14 As I look back at these experiences, it is worth considering some lessons learned, and what remains to be learned, about their use.

Lesson #1: MBS Purchases Provided Clear Benefits

Research largely provides evidence that the LSAPs that the Fed conducted since reaching the zero lower bound (ZLB) in 2008 put downward pressure on longer-term interest rates and eased broader financial conditions, helping to improve macroeconomic outcomes. Estimates of the magnitude and persistence of the effects of the Fed’s purchase programs vary, as do assessments of the relative importance of the possible channels through which such programs are believed to work.15 Further, the importance of specific channels could have varied given distinct market conditions and economic environments at the time each program was initiated.

In LSAP 1, announced in November 2008, agency MBS purchases had a stated purpose to "reduce the cost and increase the availability of credit for the purchase of houses, which in turn should support housing markets and foster improved conditions in financial markets more generally."16 This was a period of severe financial market turmoil and deep recession, so private sector buyers of MBS were on the sidelines, causing agency MBS spreads to be “abnormally” high due to market illiquidity and dysfunction. Research suggests that this purchase program reduced the portion of agency MBS spreads that was specifically considered to be “abnormal” by about 70 basis points over its first six months.17 In the framework noted above, these LSAPs worked primarily through the market functioning channel. However, research also suggests that borrowing costs were lowered more broadly through a portfolio balance effect as lower agency MBS spreads are required to induce existing investors to rebalance their portfolios into other securities.18 Overall, the Desk's purchases, aided by the FOMC’s lowering of its overnight federal funds target to the ZLB, resulted in lower mortgages rates, which in turn reduced the cost of home purchases and allowed existing borrowers to refinance at more attractive terms.

LSAP 3, an outcome-based program that included purchases of $40 billion of agency MBS per month, was launched in September 2012, after the liquidity and market functioning of agency MBS had largely normalized. As the pace of economic growth remained modest, purchases were intended to provide overall policy accommodation by putting additional downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, making broader financial conditions more accommodative, and providing further support to mortgage markets.19 Consistent with these objectives, research suggests that MBS purchases in LSAP 3 worked primarily through the reduction of the general level of interest rates, with both agency MBS and Treasury security purchases having a similar effect on agency MBS yields and likely operating through the first four channels I noted earlier.20 While MBS purchases also lower MBS yields through the prepayment channel, a further benefit of agency MBS purchases during LSAP 3 may have been in facilitating a faster pace of long-term debt purchases by the Fed, relative to only purchasing sovereign debt. In doing so, agency MBS purchases enhanced the effects of the duration and portfolio balance channels by increasing the expected stock of the central bank's total longer-term debt holdings. In contrast to LSAP 1, it seems clear that LSAP 3 predominantly worked through channels other than the market function channel.

Lesson #2: The Fed Could Purchase Large Amounts of MBS without Damaging the Market

Absent a conflicting policy objective, a central bank should aim to promote good market functioning in its operations to help ensure effective transmission to the rest of the financial system. As such, the Desk considered how to execute asset purchase programs in ways that avoided market disruption. If the Fed became too dominant a buyer or holder, it could have reduced the tradeable supply of targeted securities and discouraged trading among market participants, leading to diminished liquidity and price discovery, which could ultimately raise borrowing costs and undermine the program’s policy goal.

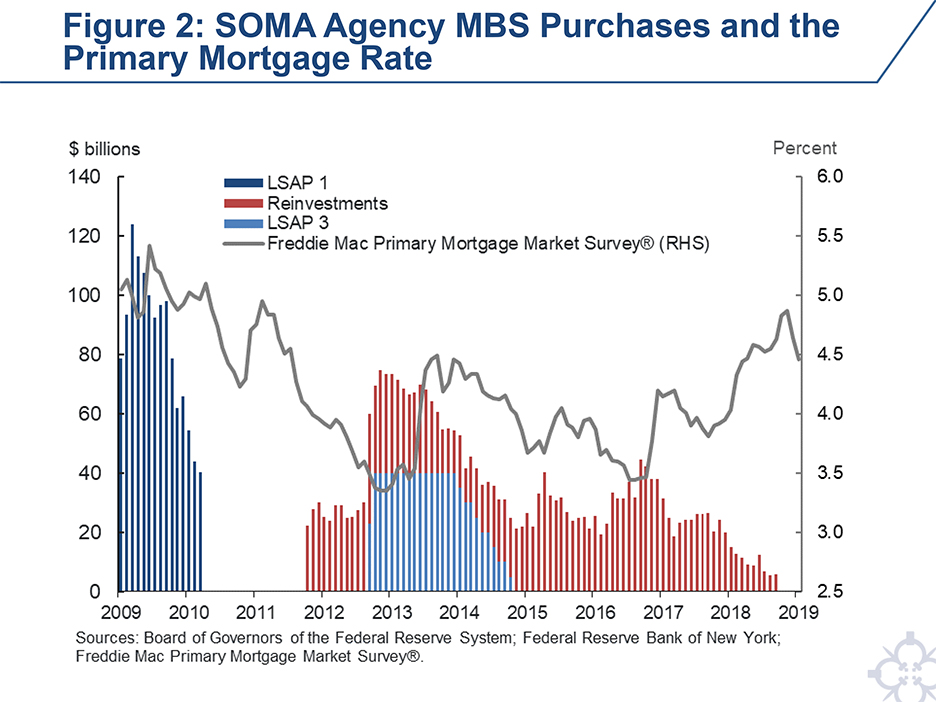

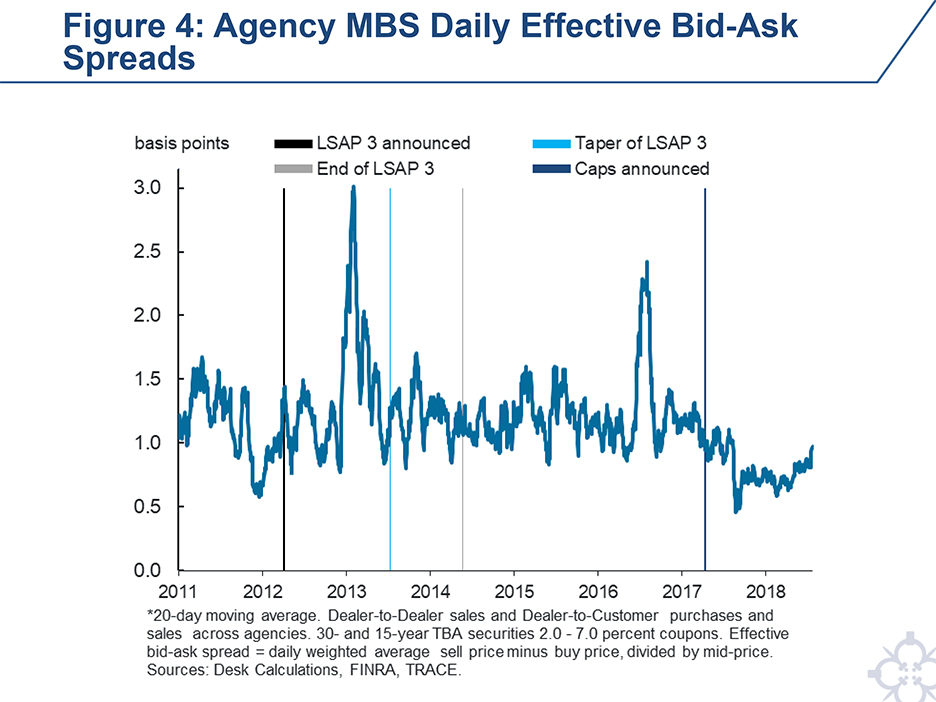

Purchases of agency MBS exceeded $100 billion per month at times in LSAP 1 and at times exceeded $70 billion per month in LSAP 3 when including reinvestment-related purchases (Figure 2). Staff actively monitored indicators of market functioning for signs of any material deterioration, and I do not believe the Fed’s purchase programs had any material unintended adverse effects.21 Transaction volumes dropped off from 2012 into 2013 as LSAP 3’s agency MBS purchases commenced, but remained fairly constant at those levels following the end of LSAP 3 (Figure 3). Bid-offer spreads implied from actual transactions have remained fairly constant since 2011, other than brief spikes following significant moves in long-term interest rates during the taper tantrum in 2013 and following the 2016 U.S. Presidential election (Figure 4). Finally, MBS fails were fairly high from 2009-2011, but fell off fairly substantially after the Treasury Market Practices Group recommended a fails charge in February 2012 (Figure 5).22

Lesson #3: Maintain Flexibility

The Fed also evolved its purchase strategies and put in place active policies to help prevent market dysfunction as a result of its operations. The initial purchase strategy targeted purchases in line with the outstanding stock of agency MBS, guided by commonly referenced market indices.23 This guidance was relaxed when the FOMC increased the size of LSAP 1 in March 2009, after which supply and demand conditions were considered. Eventually, in 2011, the Desk targeted purchases towards newly issued TBA securities, which tend to be the most liquid and readily available.24 In addition, purchases were spread across settlement months when necessary, and dollar rolls were used in a more transparent way to facilitate the orderly settlement of unsettled purchases.25

Lesson #4: Reinvestments Matter

Relatively quickly, the Fed came to learn that the reinvestment of principal payments received from securities held in its portfolio represented a distinct balance sheet tool that could help to maintain the FOMC’s desired level of monetary policy accommodation.26 This is because, in addition to the acquisition of securities through asset purchases, the period over which the central bank intends to hold its securities helps to shape market participants’ expectations about the size and duration of assets available to the public. Extending the holding period through reinvestments prolongs this so-called stock effect on the various transmission channels.

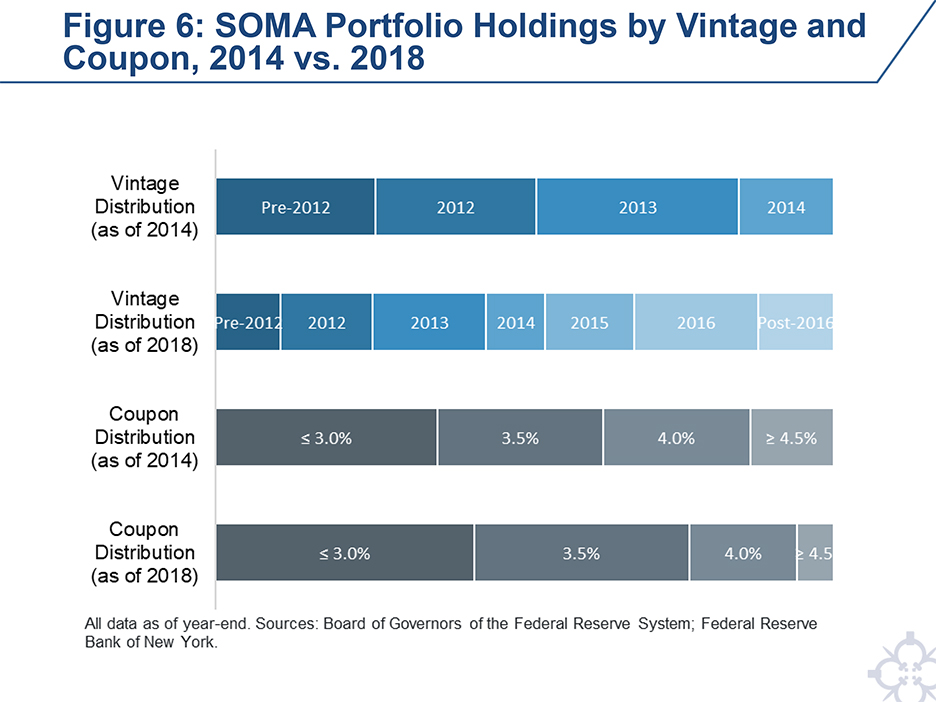

Initially after the completion of LSAP 1 in 2010, the Fed was not reinvesting agency-related principal payments and the level of accommodation provided through each of the transmission channels likely partially reversed. Though these paydowns occurred over time, they amounted to a considerable reduction in the Fed’s agency MBS portfolio, with the $1.25 trillion purchased through the end of LSAP 1 in mid-2010 falling to about $800 billion by late 2011, when reinvestment of agency MBS principal paydowns into agency MBS were initiated. Once they began, cumulative agency MBS reinvestments summed to about $2 trillion through 2018—essentially 100 percent turnover of just over $2 trillion in agency MBS purchases through LSAPs. Figure 6 highlights the evolution of certain portfolio characteristics since the end of 2014.

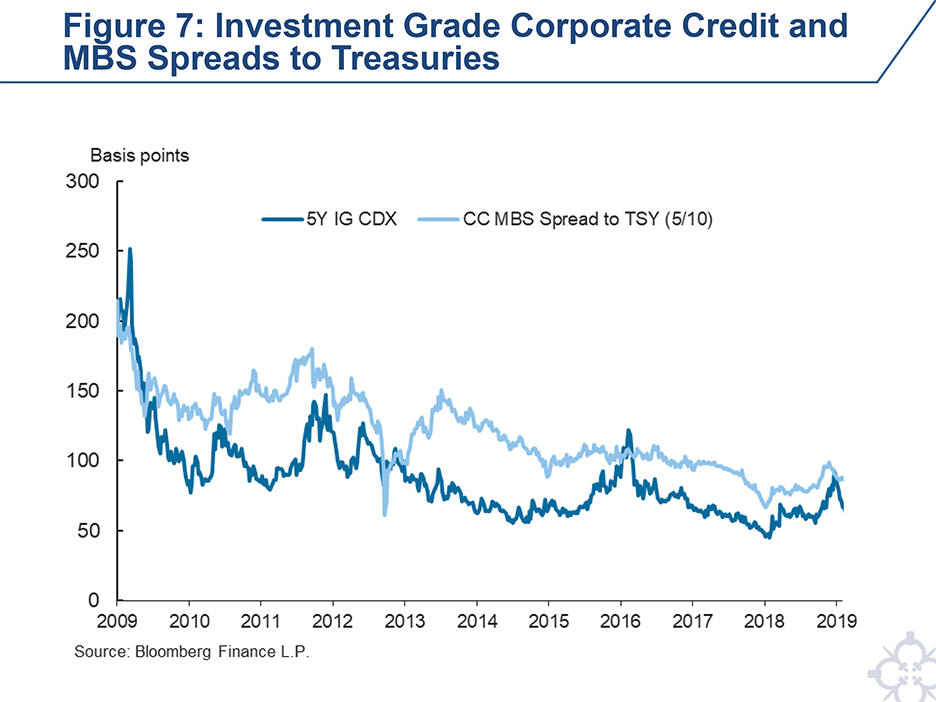

While much has been learned from our experience purchasing agency MBS, there is still room for further study. Very little is known about the effects that agency MBS purchases have on other non-sovereign assets. For example, consistent with the portfolio balance channel, market participants widely expressed a belief that agency MBS purchases had a positive effect on corporate bonds, and even equities, which may more directly influence economic outcomes. However, there has been little academic analysis to quantify this hypothesis, posing a potentially important area for additional study (Figure 7).

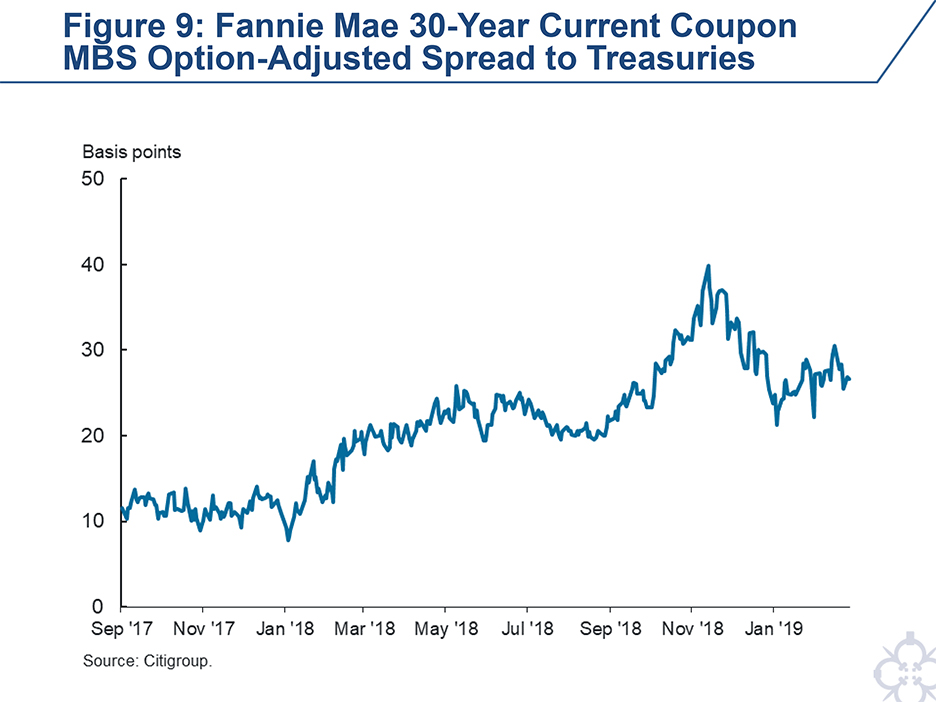

Balance Sheet Normalization

Following the end of agency MBS purchases in late 2014, principal paydowns were fully reinvested until late 2017. Starting in late 2017, the Federal Reserve has decreased its agency MBS holdings by reinvesting principal maturities only to the extent that they exceed monthly caps that gradually increased up to a maximum level (Figure 8).27 This gradual and predictable approach is intended to reduce the balance sheet’s size at an appropriate pace while supporting good market functioning and mitigating the risk of sharp or outsized asset price reactions.28 Consistent with a gradual decline in the Fed’s agency MBS holdings, 30-year MBS option-adjusted spreads (OAS) have moved modestly higher, and respondents to the Desk’s January surveys expect approximately an additional 10 basis point increase in OAS in 2019 (Figure 9).29 This gradual increase in OAS may reflect the FOMC’s gradual and predictable approach to balance sheet normalization, but could also reflect additional factors. While uncertainty exists as to the precise impact of LSAPs and the relative importance of the various transmission channels, there is even less experience to draw upon in evaluating LSAPs’ reversal, making this another area for additional study.

Preparedness for Future Potential MBS Operations

A separate challenge for the central bank to consider is how to maintain operational and analytical readiness over the long term as current operational needs evolve. For example, the Fed had no operational experience transacting in the agency MBS market prior to the crisis. It initially relied on outside investment advisors to support its first purchase program, before eventually bringing trading operations in house and then later, developing capabilities to conduct auctions on its proprietary auction platform.30 Doing so involved building out new operational practices and procedures, legal documentation, governance and reporting processes, counterparty administration, technological systems, and scaling learning curves for both central bank staff and market participants. In order for the Desk to be prepared for a wide variety of scenarios in the future, including sales or additional purchases, the Desk tests its capabilities through small-value exercises. These exercises are matters of prudent advance planning and portfolio administration by the New York Fed, and no inference should be drawn about the timing of any change in the stance of monetary policy in the future from them.

In the near term, Figure 8 shows that current market pricing implies that no further agency MBS reinvestment operations will be necessary during the normalization process. But since principal payments on agency MBS are sensitive to changes in long-term interest rates and other factors, it is possible they could rise above the cap and require some agency MBS reinvestment purchases in the future.31 In light of this possibility and in the interest of operational readiness, the Desk has been purchasing up to $300 million of agency MBS for monthly periods in which principal payments fall below the cap and there are otherwise no reinvestments.32

Agency MBS sales are not part of the process of normalizing the size of the balance sheet; however, it was noted in the minutes of the December 2018 FOMC meeting that “Several participants commented on the possibility of reducing agency MBS holdings somewhat more quickly than the passive approach by implementing a program of very gradual MBS sales sometime after the size of the balance sheet had been normalized.”33 To date, the Federal Reserve's experience conducting sales of agency MBS has been limited to small-value exercises that have been run semi-annually since 2015. There would be more to learn about selling agency MBS prior to any decision to use gradual sales to normalize the composition of the balance sheet.34 From a practical standpoint, sales may be complicated in that they would most likely be conducted through sales of individual securities, rather than through the TBA market, because the securities in the SOMA portfolio would most likely be more valuable than those that are cheapest-to-deliver into TBAs.35

In addition, the structure of the agency MBS market is expected to change with the June 2019 implementation of the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s Single Security Initiative. Under this initiative, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBS are expected to be harmonized such that they can be traded in a single TBA contract, known as Uniform MBS (or UMBS). This change is expected to improve the liquidity of the agency MBS market and would simplify any future agency MBS purchase operations for the Desk. The Desk is developing its operational readiness for transacting in UMBS and will likely conduct operational readiness operations in UMBS later this year.36

Conclusion

In discussing its balance sheet reaction function in its Policy Normalization Principles and Plans, the FOMC has noted that it is prepared to alter size and composition of the balance sheet if future economic conditions were to warrant a more accommodative monetary policy than can be achieved solely by reducing the federal funds rate. However, the Committee has given no indication whether agency MBS would be included in future securities purchase programs. From an implementation perspective, the Federal Reserve is fortunate to have the option of implementing monetary policy in a large and liquid non-sovereign market with direct implications for existing and prospective homeowners, in addition to the U.S. Treasury market where it has the capacity to buy large amounts at a fast pace as illustrated by former Chair Janet Yellen in a speech at Jackson Hole in 2016.37 However, future policymakers will need to weigh these benefits versus credit allocation concerns in making that determination.