Good morning, and thank you to the Brookings Institution-Chicago Booth Task Force on Financial Stability for convening this discussion on such a critical topic. This has been a year marked by tremendous human suffering related to the pandemic and unprecedented challenges for the global economy and financial markets. The events that unfolded in March and April underscored the importance of understanding market functioning and liquidity so that financial markets continue to serve their important role in supporting the economy.1

In the first quarter of 2020, the global financial system experienced an extraordinary shock, triggered by the coronavirus pandemic. Asset prices adjusted sharply, reflecting increasing pessimism and uncertainty about the economic outlook as large segments of the economy began to shut down. A spike in financial market volatility, combined with concerns about markets’ ability to function in a remote work environment, resulted in a surge in the demand for cash.

The Federal Reserve took swift and decisive action in response to both the shift in the economic outlook and deteriorating conditions in financial markets.2 The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) cut the target range for the federal funds rate close to zero, and directed the Open Market Trading Desk (the Desk) to conduct repo operations and purchases of Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to support the smooth functioning of these markets. The Federal Reserve undertook a wide range of additional steps—many in coordination with the U.S. Treasury—to support the flow of credit to households, businesses, and state and local governments. Regulations were also temporarily adjusted to encourage bank lending. These comprehensive actions, alongside swift passage of the CARES Act to support the U.S. economy, were essential for stabilizing U.S. financial markets and averting an even deeper collapse in economic activity.

The disruption in the U.S. Treasury market was especially notable, as measures of market functioning deteriorated at unparalleled speed to levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis. The Treasury market is the deepest and most liquid fixed-income market in the world. It serves as a critical benchmark for all other dollar fixed-income markets, both in the U.S. and abroad, including the mortgage, corporate debt, and municipal bond markets that are essential to the flow of credit. Given the importance of the Treasury market, continued dysfunction could have led to an even deeper and broader seizing-up of credit and ultimately worsened the economic hardships that many Americans have been experiencing.

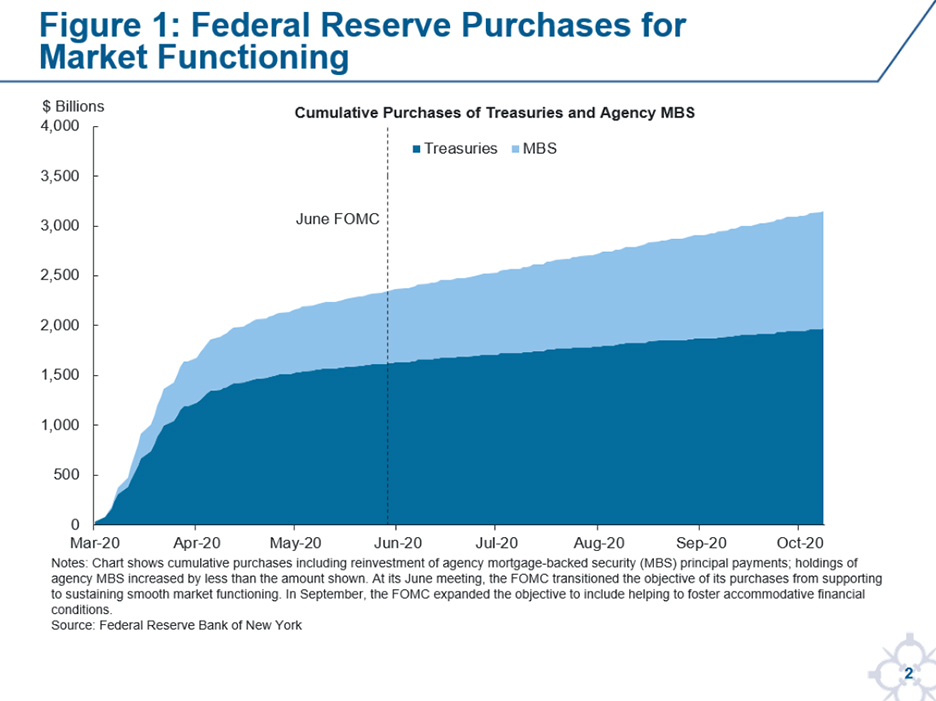

The Desk initially responded to the severe dysfunction by expanding repo operations, and then, at the direction of the FOMC, by buying a substantial quantity of Treasury securities and agency MBS. The FOMC then demonstrated a more forceful commitment by directing the Desk to purchase these securities “in the amounts needed” to support smooth functioning of these markets. The speed and scale of these actions—and the flexibility with which they were deployed—stabilized and eventually restored market functioning, and in June the FOMC transitioned the objective of purchases to sustaining smooth market functioning. During the period from March to June, the Federal Reserve purchased a total of around $1.6 trillion of Treasuries and $700 billion of agency MBS, as shown in Figure 1.3

In recent months, the public and private sectors initiated broad-based efforts to better understand the dynamics that led to the Treasury market dislocation in March and April. Ongoing research is helping shape our views of what happened, and last month the New York Fed, along with other Joint Member Agencies, co-hosted the sixth annual U.S. Treasury Market Conference.4 Participants focused on the causes of the Treasury market disruption and potential measures that could be taken to ensure the market’s resilience going forward.

Today, I want to share some observations from our experience executing open market operations on the Desk during this period, and from the developing body of research and discussions. I would note that the views I express today are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

What Have I Taken Away from the Data and Research So Far?

Data and developing research offer perspective on important elements of the events of last spring. Though many aspects of what occurred warrant further study, I would like to focus my remarks on insights that the data and research provide about the exceptional desire to sell Treasury securities, and the capacity of the Treasury market infrastructure to manage these flows.

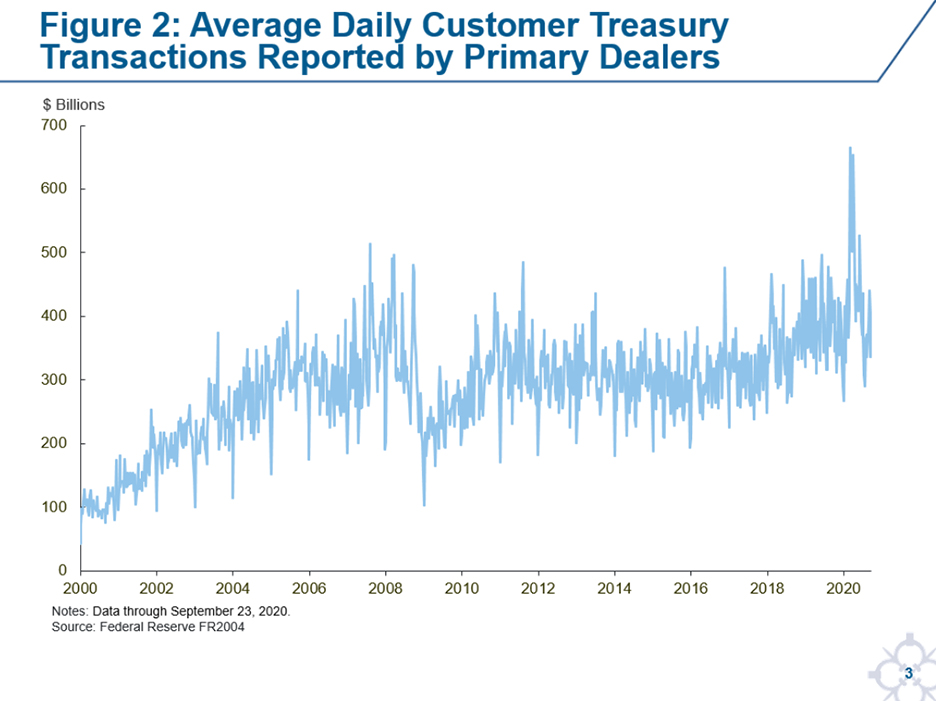

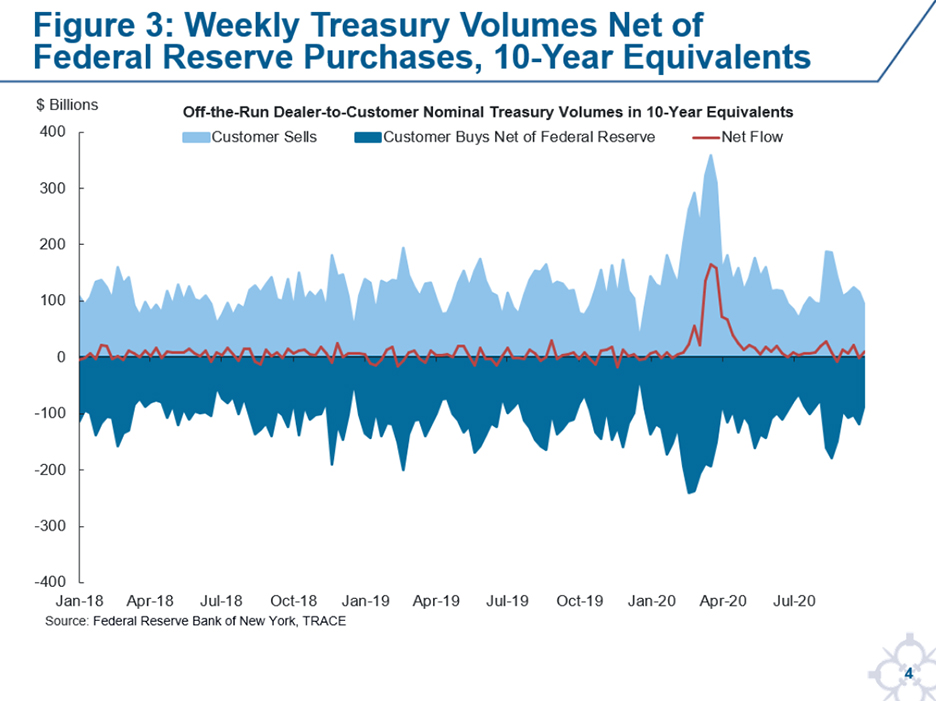

On the Desk, we certainly heard from our contacts and observed in the data available to us at the time that there was an extraordinary volume of selling by Treasury investors. Since then, data have confirmed that the size of those sales was unprecedented. As shown in Figure 2, customer transaction volumes reported by primary dealers spiked from an average level of around $400 billion per day in February to a peak of around $650 billion per day in mid-March—an increase of more than 50 percent. The more granular data from the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) confirm that the size of the risk being transferred was exceptional. The top half of Figure 3 shows the volume of daily customer sales of off-the-run Treasury securities expressed in “10-year equivalents,” a measure of the dollar amount of securities normalized by their interest rate risk.5 The bottom half shows customer purchases, net of the Federal Reserve’s purchases. The difference between these, in red, highlights the extraordinary degree of market liquidity being demanded by customers.

We also observed in March and April that these sales of Treasury securities were coming from a wide range of investors. While some commentary since then has focused on the role of certain investor types and strategies, recent data and work by academics help to dimension the broad-based nature of the selling.6

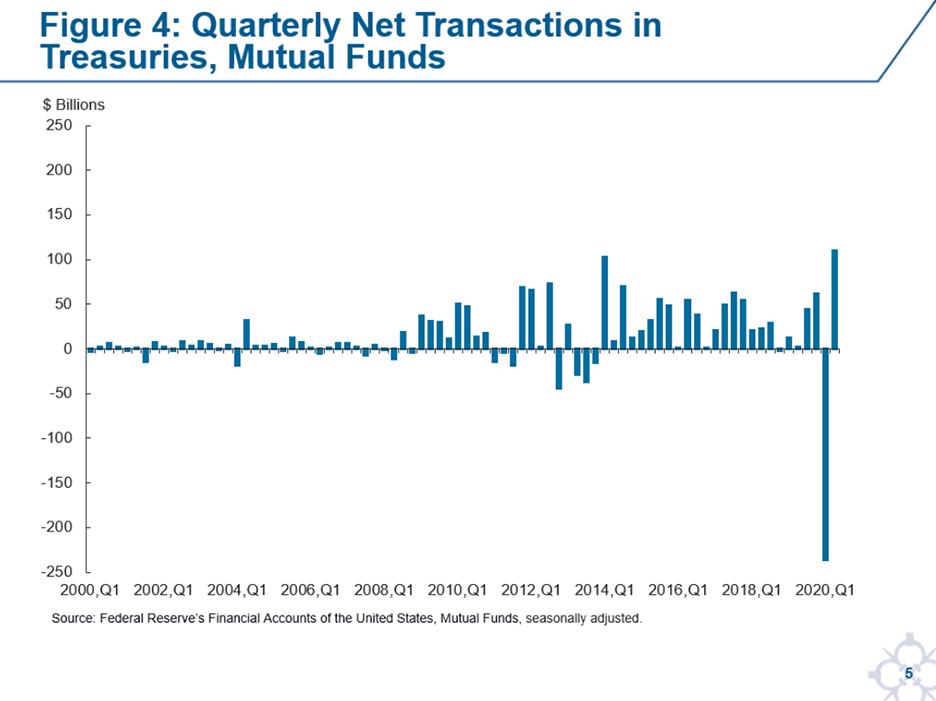

Mutual funds appear to have sold in exceptionally large volumes, as these funds monetized their most liquid asset holdings to prepare for potential redemptions and rebalance their portfolios. As shown in Figure 4, net sales of Treasuries by domestic mutual funds totaled almost $200 billion in the first quarter, the largest quarterly decline on record.7

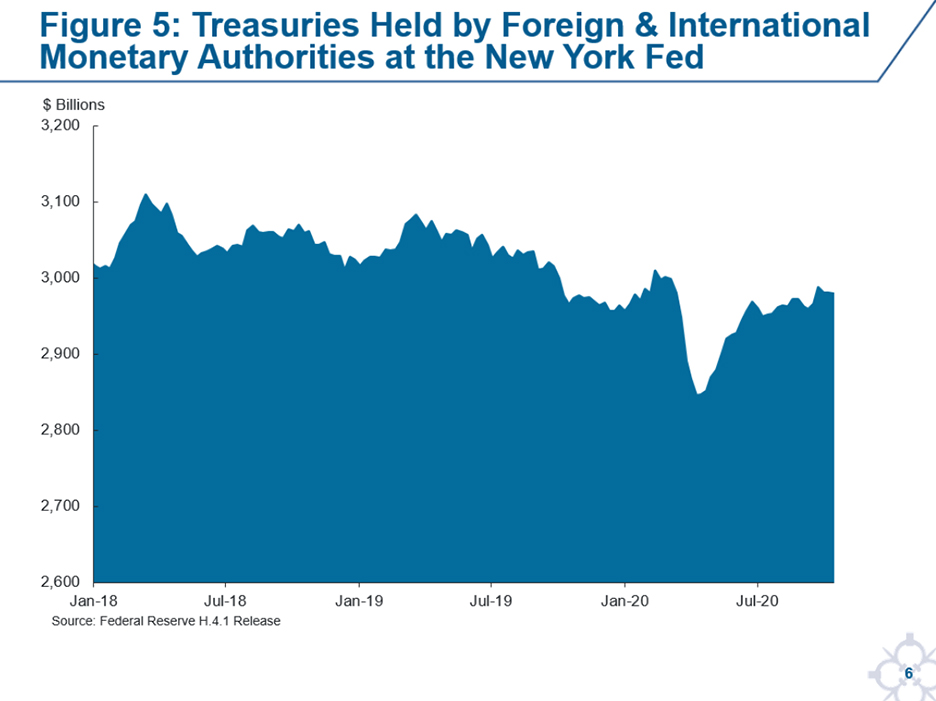

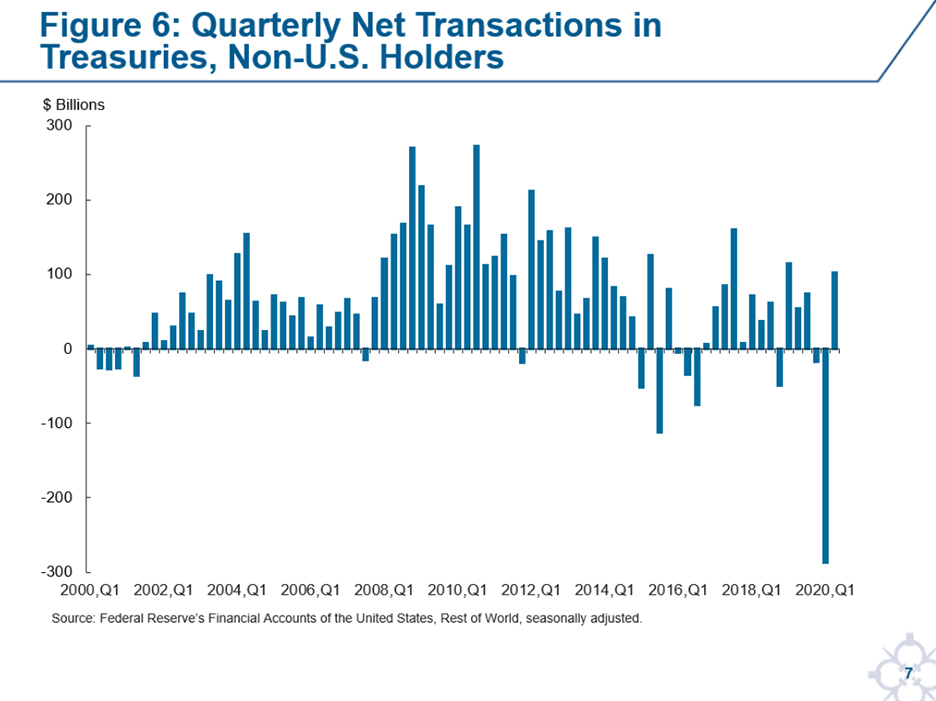

Foreign official accounts, some of which were raising funds to meet actual and anticipated local needs for U.S. dollars, were also large net sellers, as shown by data from official accounts held at the New York Fed depicted in Figure 5. According to data from the Federal Reserve’s Financial Accounts of the United States, shown in Figure 6, foreign accounts, both official and private, sold a meaningful amount of Treasuries in the first quarter, although these data also include funds that operate in the U.S. but are domiciled offshore.

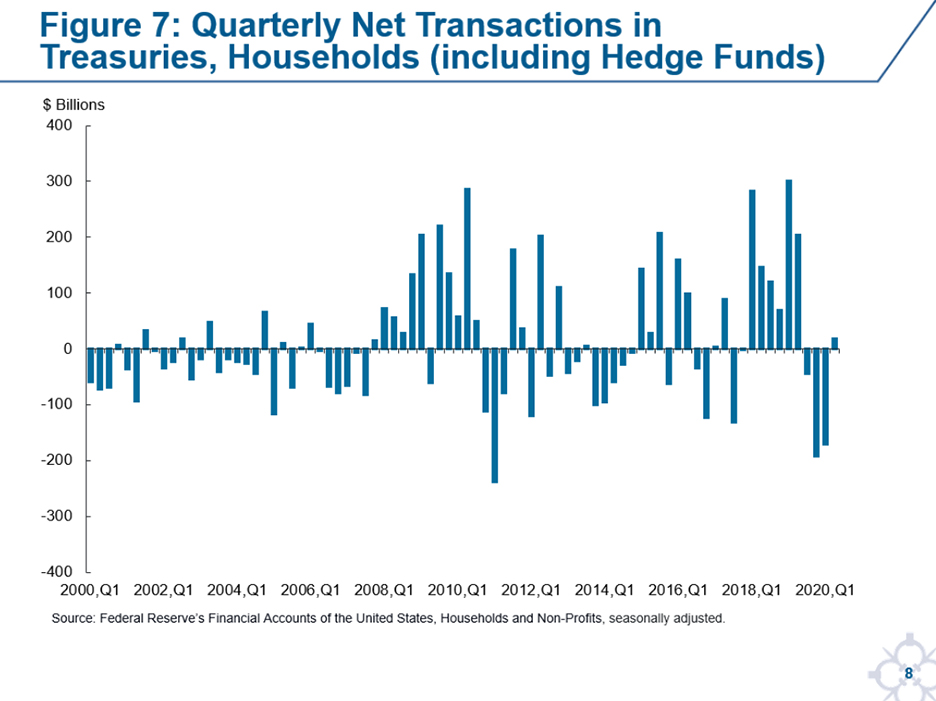

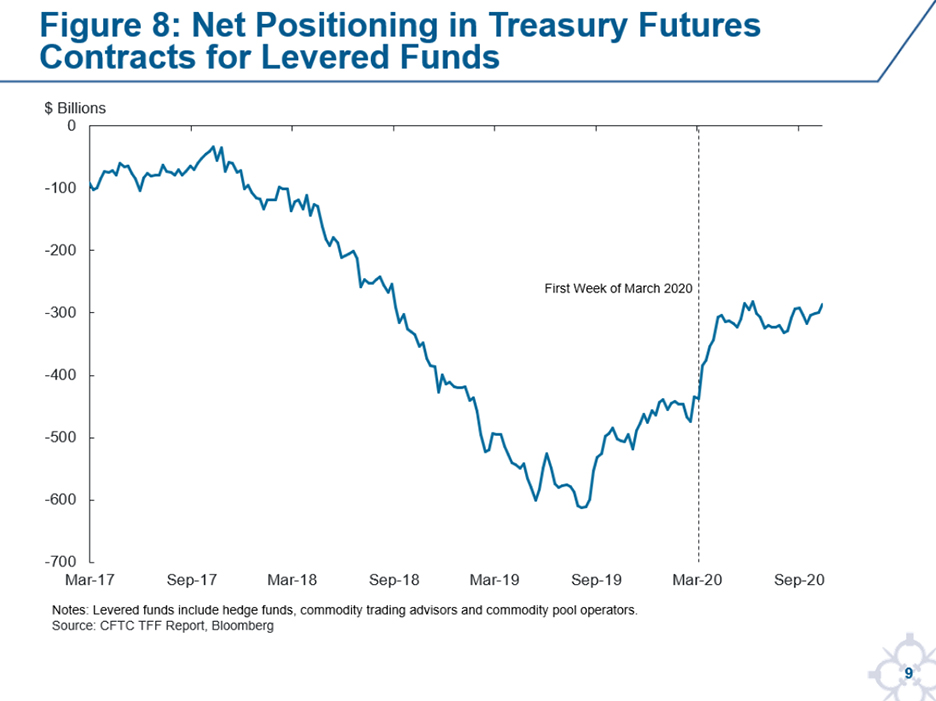

There has been significant attention on hedge fund sales of Treasury securities, and whether these amplified the stresses in the Treasury market. We heard in March and April that the sharp increase in volatility and futures margins resulted in relative value funds and other levered strategies reducing their positions.8 According to the U.S. Financial Accounts data, net sales of Treasury securities by households—a category that includes private investors domiciled in the U.S.—were notable in the first quarter, shown in Figure 7.9 We also observed that the reduction in net short positions in Treasury futures held by levered accounts accelerated sharply in March, as shown in Figure 8. Some research papers attribute a significant degree of the stress to hedge funds unwinding cash-futures basis positions, while others question whether these strategies were a meaningful contributor to the dynamics.10 This is difficult to judge, in large part because the available data on hedge fund holdings and transactions are incomplete. In the context of broad-based selling pressure, though, I think of these sales as an important contributing factor, but not the sole source of the challenges.

In addition to giving greater insight into the historic size and breadth of sales, data and recent research shed light on how the Treasury market responded to these extraordinary flows.

Before diving into this, I’d like to start with some background on the ecosystem of Treasury market intermediation. Broadly speaking, trading takes place in two separate but connected market segments: the dealer-to-client segment, where dealers transact with end-investors, and the interdealer segment, which is generally comprised of dealers and principal trading firms, or “PTFs,” trading with one another in the most liquid securities and largely on electronic limit order books.11 The interdealer segment is critical to the intermediation process, as it allows participants to manage risk and adjust positions rapidly and serves as an important source of price discovery in Treasuries. These features support the intermediation of customer flows and the smooth functioning of the Treasury market overall.12

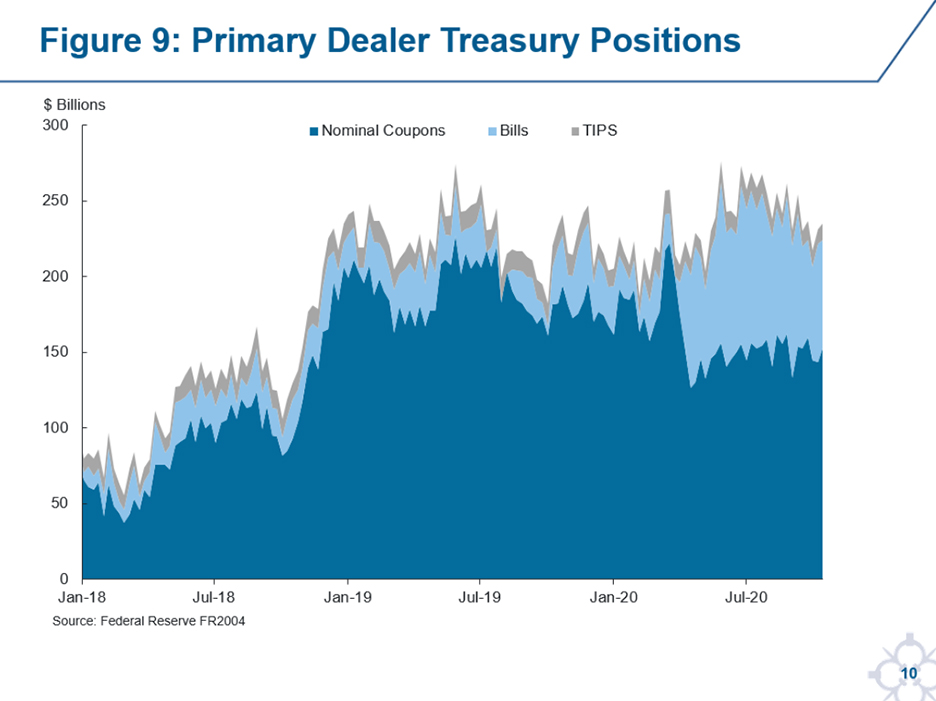

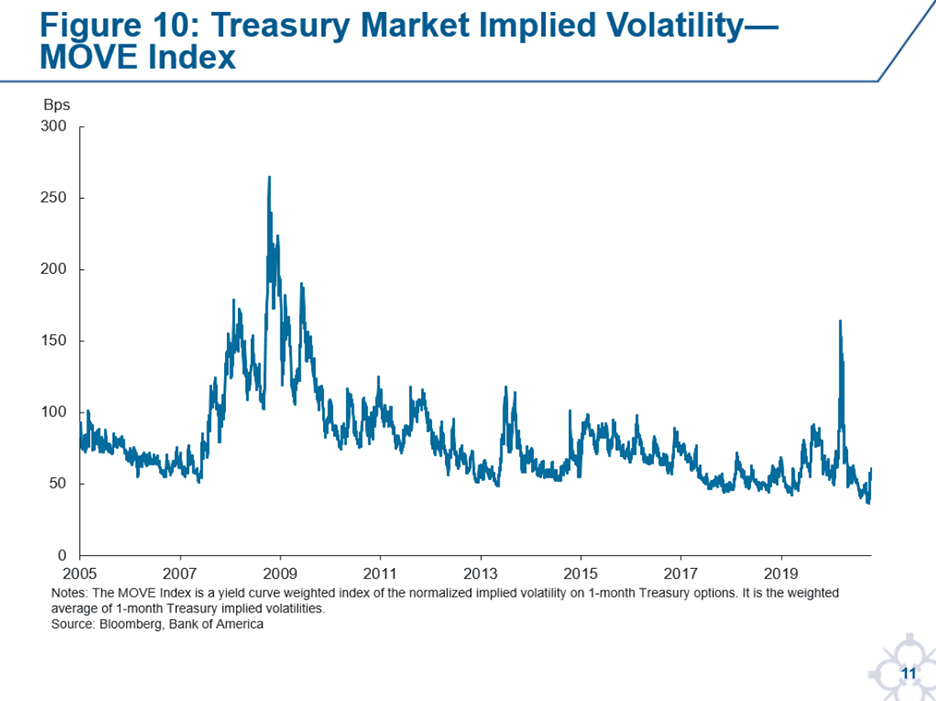

Our observations in March and April were that these intermediation channels became highly strained. The data show that dealers entered March with inventories of Treasury securities that were already high by historical standards, and, as depicted in Figure 9, those inventories grew as investors sold securities. Our conversations with dealers suggest that, amid a sharp increase in perceived risk, it became increasingly challenging to hold these positions and absorb new ones. In March, volatility in Treasury markets soared to levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis, as shown in Figure 10.13 Heightened volatility increases the risk that dealers face in intermediating markets, as prices have greater potential to move during the period between the purchase and sale of securities. In this environment, dealers noted that risk measures rose sharply, and many suggested that internal risk management processes developed to ensure compliance with regulations limited the nimbleness with which they could respond to rapidly evolving circumstances.

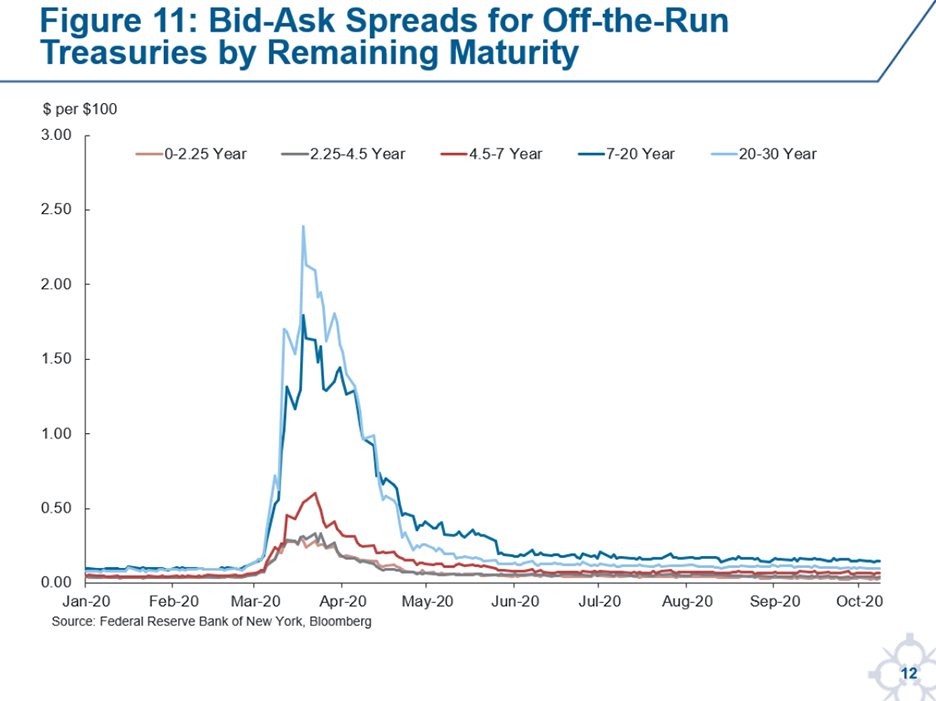

In an environment of extraordinary volatility and large Treasury sales, the terms on which dealers were willing to make markets deteriorated sharply. For example, in less liquid off-the-run Treasury securities, bid-ask spreads, which are a measure of the price that investors pay to transact, rose to almost 30 times their normal levels and reached historic wides, as shown in Figure 11.

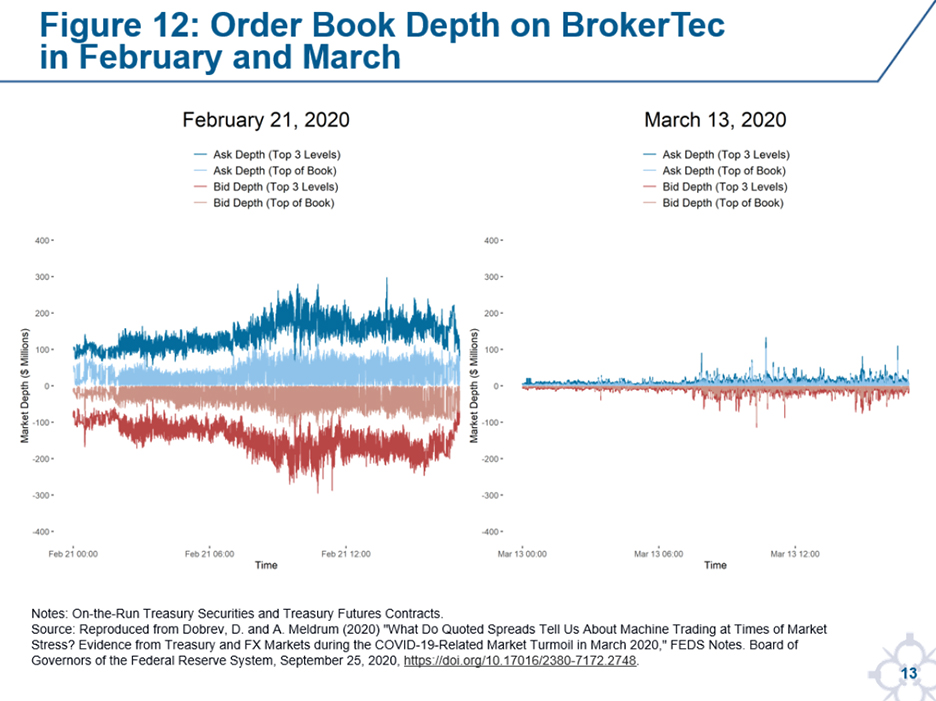

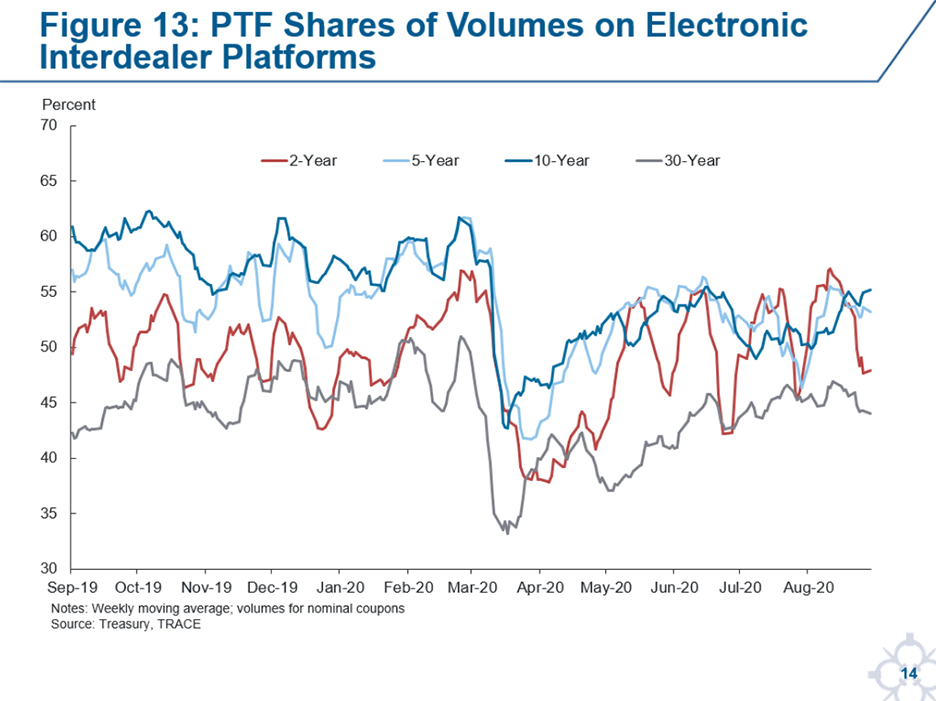

Deteriorating conditions in the interdealer market likely exacerbated the challenges that dealers faced providing market liquidity to their customers by limiting their ability to efficiently manage risk. As highlighted in a recent note by Federal Reserve economists Dobrislav Dobrev and Andrew Meldrum, market depth in on-the-run Treasury securities fell dramatically compared to typical levels, and standing orders near the top of the order book on electronic systems were not replenished rapidly enough to keep pace with increased trading volumes. Figure 12, reproduced from their note, illustrates this sharp drop in market depth, showing the top level and top three levels of the order book on a normal day, on the left, and on a highly stressed day in mid-March, on the right.14, 15 Liquidity providers in this market—both dealers and PTFs—faced high and unpredictable volatility and flows that made it riskier to maintain or quickly restore standing orders. Overall, PTFs, which are more thinly capitalized and do not typically hold positions overnight, appear to have reduced the competitiveness of their intermediation to a somewhat greater degree, as their share of transaction volume fell, depicted in Figure 13.16

Nonetheless, it seems important to note that while the terms on which Treasuries were intermediated deteriorated dramatically, a much higher-than-normal volume of private transactions still occurred. So, while liquidity was severely strained, the volume that intermediaries were managing was still quite high, even in the less liquid market segments such as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) and off-the-run Treasury securities.

In sum, I interpret the work to date as confirming our observations at the time that unprecedented demand for cash led to selling that was historic in size and broad-based in nature. Intermediation activity expanded, but was unable to keep pace, and the market came under severe strain. As a result, the Fed stepped in to buy securities at unprecedented scale and speed, ultimately restoring and sustaining effective market functioning.

What Ideas Have Been Raised That Could Make the Market More Resilient?

At the U.S. Treasury Market Conference, there was an insightful and robust discussion among industry professionals, academics, and policymakers about Treasury market resilience.17 While participants acknowledged that there is still much more to learn about the events of March and April, many shared early ideas on how the resiliency of this critical market might be enhanced over time.

Financial markets are always evolving in response to changes in the environment, including technology, regulation, and business models. Participants at the conference noted that, in recent years, we have seen substantial growth in the share of electronic intermediation, significant changes in the regulation of key intermediaries, and a meaningful shift in both the outstanding size and holders of Treasury debt.

Participants highlighted how each of these has brought substantive benefits, but may also present new considerations. Increased volume of electronic trading on central limit order books has contributed to reductions in transaction costs and lowered barriers to entry for new liquidity providers. However, available liquidity can diminish in highly volatile markets, as market makers manage risk and may have less relationship incentive to maintain liquidity provision on anonymous platforms. Regulations have enhanced financial stability by making banks and their broker-dealers more resilient, but conference participants suggested that the manner in which firms implement regulations may reduce their flexibility to respond to rapidly evolving conditions.

Finally, participants highlighted that growth in Treasury issuance has been essential for the U.S. government to support U.S. households and businesses during the pandemic, but, as Darrell Duffie noted in a recent paper, ongoing increases in the stock of Treasuries may result in greater peaks in the demand for intermediation.18 These peaks may be amplified by the reliance of some investors on Treasuries to provide liquidity in portfolios with natural liquidity mismatches, and by the use of leverage in some Treasury investment strategies.19

I was pleased that conference participants also offered some early ideas for enhancing the resiliency of the Treasury market in this evolving environment. Of course, given the complexity associated with changes to Treasury market infrastructure, I would highlight that these ideas are preliminary and all would require further analysis.

First, several conference participants suggested that, while Treasury market data has improved markedly in recent years, continuing to enhance transparency could bolster confidence in the ability to transact fairly, particularly in volatile markets.20 For repo markets, providing public data on the opaque uncleared bilateral segment could improve visibility into the size of levered Treasury positions, and data on term repo might give market participants more confidence in pricing. In the Treasury cash market, continuing to refine and increase the availability of the TRACE data would improve our understanding of the market, including the types and prevalence of trading strategies and the methods of execution.21

Second, conference participants suggested ways to increase the capacity for and flexibility of liquidity provision, so the market can manage peaks in liquidity demand. Expanding access to trading venues and central clearing were both highlighted as potential ideas. Increased central clearing can help market participants manage settlement risk and facilitate more efficient balance sheet usage, and may also pave the way for more direct trading among Treasury market participants.22, 23 Separately, several conference participants thought it might be helpful to explore whether adjustments to certain regulations might enhance banks’ flexibility, while still maintaining their resiliency.

Third, and finally, participants highlighted steps that could help stem the volume of sales during periods of high volatility and stress. Several indicated that greater uniformity or enhanced transparency in margin practices could reduce the need for funds employing certain levered trading strategies to unwind positions amid higher volatility. In addition, some thought further study may be warranted on the role of nonbank financial institutions in this market. With regard to the Federal Reserve, participants suggested that existing repo backstops could be fortified, as these facilities provide confidence in the liquidity of Treasuries, thus reducing the need for outright Treasury sales during stress events.24

Conclusion

In sum, the pandemic created exceptional uncertainty about the economic outlook and concern about financial market functioning, resulting in an intense demand for cash. This desire to raise cash rapidly, combined with extraordinary financial market volatility, resulted in an unprecedented volume of Treasury sales and stresses in the Treasury market. In response, the Federal Reserve stepped in to support the smooth functioning of this vital market in order to maintain the flow of credit to U.S. households and businesses.

This was truly an exceptional event. However, while it is tempting to dismiss it as a once-in-a-lifetime shock, it is important to take time to reflect and assess if lessons can be learned that could make the Treasury market even more resilient to future shocks. The situations that require policy intervention should be extraordinarily rare.

In this regard, I have been heartened by the energy that academics, industry professionals, and public sector officials have brought to understanding the underlying drivers of the stress in March and April. The developing research and discussions are already producing vital insights, and I encourage continued engagement on these issues. I also look forward to working together with other agencies and industry professionals to explore ways to enhance the resilience of the U.S. Treasury market, so that it continues to be the deepest and most liquid fixed-income market in the world.

Thank you, and I look forward to the discussion.