Thanks very much for that kind introduction. I would like to thank Dick Berner and Venky Venkateswaran for organizing this event.1 As Dick would likely recall, I was supposed to give a talk about implementing policy here at NYU Stern two years ago, almost to the day. We had to cancel that speech as it became clear that the emerging pandemic and the efforts to contain it would disrupt the global economy and lead to unprecedented strains in financial markets. Today, the world faces an extraordinary new challenge. I would like to acknowledge the tragic events in Ukraine and the terrible hardship this places on the Ukrainian people. The economic and financial impact of these events will take time to become clear. On the Desk, we are monitoring global developments carefully.

My remarks today will begin by looking back at the pandemic crisis and the historic policy response. Starting in March 2020, the Federal Reserve took a set of extraordinary measures in response to the extreme economic stresses and dislocations in the global financial system that were triggered by the pandemic. These actions—many taken in close coordination with the U.S. Treasury, and alongside a forceful fiscal response from the U.S. government—were successful in providing accommodation to the U.S. economy during a very vulnerable and uncertain period.2

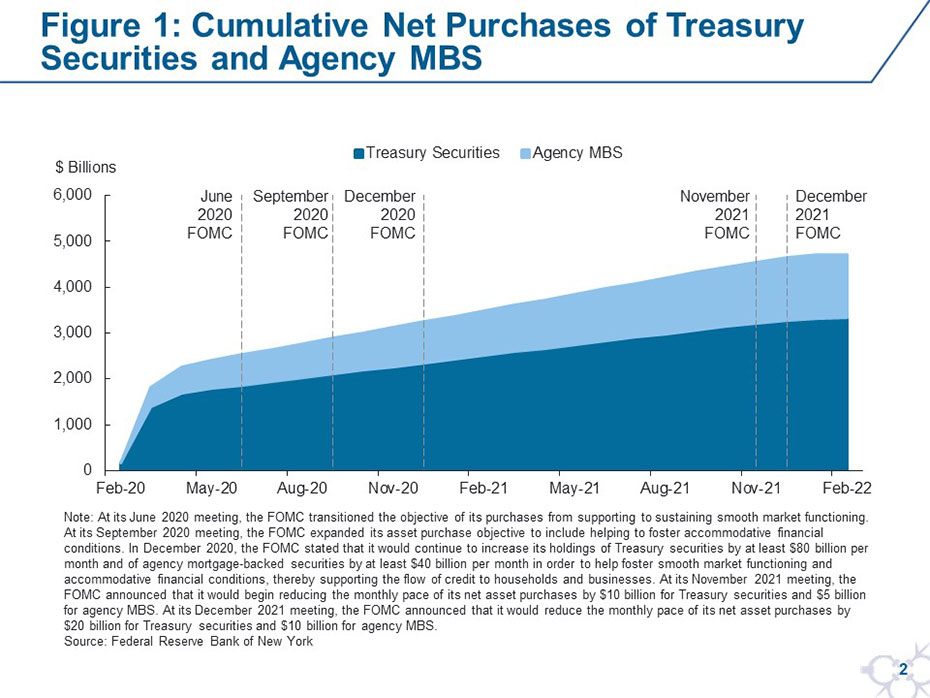

In light of recent strength in the labor market and elevated inflation, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has decided to end net purchases of Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in early March. The Committee also stated that it expects it will soon be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate, and released principles for significantly reducing the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.3

With net asset purchases coming to an end, it is an opportune time for reflection. In my remarks today, I’ll first review the asset purchases the Fed conducted over the past two years, exploring how the Committee’s evolving objectives for these purchases influenced the Desk’s implementation approach. I’ll then highlight how these purchases shaped the SOMA portfolio today and discuss some considerations ahead for policy implementation, in the context of the FOMC’s recently issued Principles for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet.

As always, the views I express today are my own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.

The Fed’s Asset Purchases: Objectives and Implementation

Next week, the FOMC’s net purchases of Treasury securities and agency MBS will come to an end, marking the conclusion of this historic program, in which net purchases totaled roughly $4.6 trillion, as shown in Figure 1. These purchases were instrumental in supporting the flow of credit to the U.S. economy and fostering accommodative financial conditions—and, along with other significant policy measures, prevented a much deeper economic downturn.

The onset of the pandemic resulted in an unprecedented “dash for cash” as heightened uncertainty in the outlook and shifts to a remote trading posture prompted extreme price volatility, sudden portfolio de-risking, and strains in market functioning. In this environment, even the most liquid securities, like Treasuries, were being sold broadly and in large quantities, overwhelming the market’s intermediation capacity.4

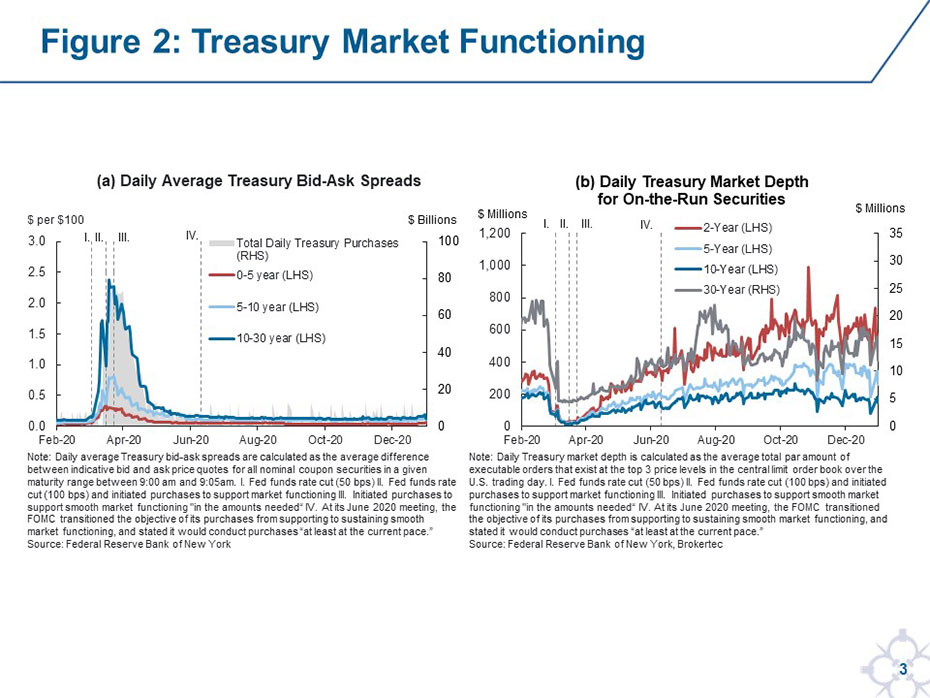

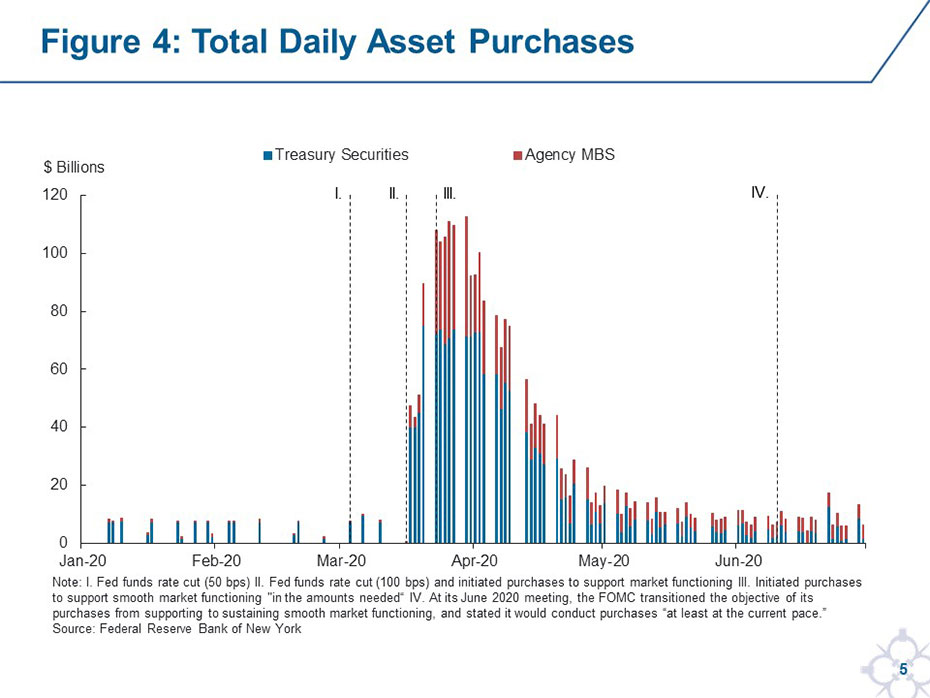

By mid-March 2020, Treasury and agency MBS market functioning had deteriorated to levels not seen since the Global Financial Crisis. In this truly exceptional environment, the Fed stepped in to buy securities at an unprecedented scale and speed to restore market functioning and maintain the vital flow of credit to the U.S. economy. This entailed purchasing record amounts of securities to address one-way selling flows and meet the immediate demand for liquidity.

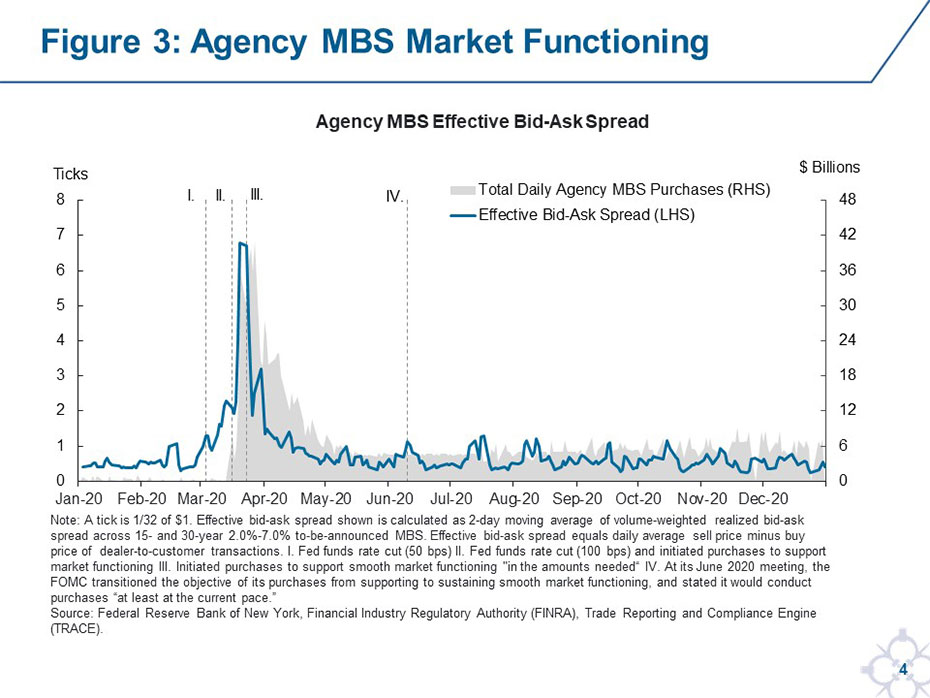

The flow of these purchases helped to alleviate private sector balance sheet constraints and meet this demand for market liquidity. Over time, purchases restored two-way trading and more normal market functioning. The FOMC’s full commitment to purchase Treasuries and agency MBS “in the amounts needed” to support smooth market functioning also had the effect of stabilizing precautionary sales and forestalling a spiral in liquidity demand.5

During this period, flexibility was a hallmark of our implementation approach. The Desk adjusted purchases in response to shifting market conditions and sized them to address dysfunction. We closely monitored and assessed market functioning metrics and targeted sectors in which conditions were especially strained. In the MBS market, operational adjustments included purchasing a broad range of securities that came under intense selling pressure and purchasing for near-term settlement, which helped ease pressures on dealer balance sheets. This differed from the Desk’s typical practice of purchasing recently produced coupons in the to-be-announced (TBA) market for forward settlement.

Given the depth of the strains, market functioning improved only gradually at first. However, with the Committee’s full commitment to supporting market functioning and the Desk’s continuous operational adjustments, market functioning metrics improved considerably over the course of several weeks, and the Desk reduced purchase amounts commensurately.6 In the Treasury market, bid-ask spreads narrowed and market depth rebounded, as shown in Figure 2. Similarly, agency MBS market liquidity conditions, as represented by the effective bid-ask spread shown in Figure 3, improved markedly.

As market functioning improved and conditions stabilized, the Committee shifted its focus to fostering accommodative financial conditions to support the economy as it recovered from the pandemic shock, and to sustaining the gains made in market functioning. While asset purchases conducted to support market functioning were used during the pandemic to address extraordinary and acute stresses, asset purchases aimed at fostering accommodative financial conditions are a standard part of the Committee’s monetary policy toolkit, employed when the federal funds rate is constrained by its effective lower bound (ELB).

By reducing the stock of securities and duration risk held by private investors, Fed asset purchases lower term premiums and longer-term interest rates, easing financial conditions broadly. In addition, purchases of agency MBS reduce the amount of prepayment risk held by investors, leading MBS spreads to fall and resulting in lower mortgage interest rates for homeowners. Asset purchases can also convey information about the FOMC’s policy intentions, as market participants believe the Committee would be unlikely to raise its policy rate while conducting asset purchases.

As the FOMC’s objectives for asset purchases evolved, so too did the operational approach. Purchase amounts were quickly scaled back as conditions improved, dropping from a daily average of over $100 billion in late March 2020 to around $10 billion by the summer, as shown in Figure 4. Without the need for high-frequency adjustments to address market strains, the Desk extended the horizon for purchase calendars to provide more predictability in planned operations. Purchase allocations also became more standard and were distributed relatively neutrally to the universe of securities outstanding. In this case, Treasury purchases were allocated proportionally to the amounts outstanding across the nominal Treasury coupon and TIPS coupon curves.7 In the MBS market, the composition of purchases was adjusted to be roughly in line with recently produced coupons in the TBA market.

Overall, the asset purchases, and the operational approach used to implement them, were effective at achieving the Committee’s objectives. The flow of purchases substantially improved market functioning by meeting immediate demands for market liquidity in strained conditions. The total stock of Fed asset holdings—resulting from both purchases initiated to address market functioning and those conducted with a focus on providing accommodation—worked to put downward pressure on longer-term yields and ease financial conditions. And, the Committee’s communications about asset purchases had important signaling effects about its commitment to supporting the economy.

What I take away from this experience is that the FOMC’s toolkit for addressing both severe market functioning disruptions and economic downturns is comprehensive and effective. Nonetheless, while asset purchases used to support market functioning and those employed to foster accommodative financial conditions may be broadly similar in nature, I do not view them as equal parts of the monetary policy toolkit. I expect circumstances warranting sizable intervention to support market functioning to be extraordinarily rare. In this respect, the ongoing work to better understand vulnerabilities in the U.S. Treasury market and to develop potential reforms to further enhance its resiliency is critical.8 In contrast, the Committee has indicated that asset purchases to provide accommodation are a standard tool when the federal funds rate is constrained by the ELB.9

Considerations for Policy Implementation Ahead

Looking ahead, as I noted, with a strong labor market and elevated inflation, the FOMC has stated that it expects it will soon be appropriate to raise its target range for the federal funds rate, and has indicated that it intends to significantly reduce the size of the balance sheet.10

For now, the FOMC has directed the Desk to continue to reinvest all principal payments from the Fed’s Treasury and agency MBS holdings following the conclusion of net purchases, which will maintain the size and broad composition of the SOMA portfolio.11 However, in recent meetings, the FOMC began deliberations on its approach to reducing the balance sheet, and following its January meeting the Committee issued principles to provide information on its planned approach.12 These principles are high-level tenets, and not specific plans. They build on the experience gained from reducing monetary policy accommodation over 2014 to 2019, and, importantly, also reflect the Committee’s assessment of the current environment.

The principles start by affirming that the FOMC sees changes in the target range for the federal funds rate as its primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy, and that reducing the balance sheet will occur after the process of raising the target range has begun. The principles further state that when the Committee decides to begin reducing its securities holdings, it intends to do so over time in a predictable manner, primarily through adjustments to reinvestments, so that securities holdings decline with principal payments. In addition, the principles affirm the FOMC’s choice of an ample reserves operating regime, and an intention, in the longer run, to hold primarily Treasury securities.

Let me turn to a couple of considerations ahead for policy implementation, in the context of these principles and the current contours of the SOMA portfolio.

SOMA Portfolio Contours

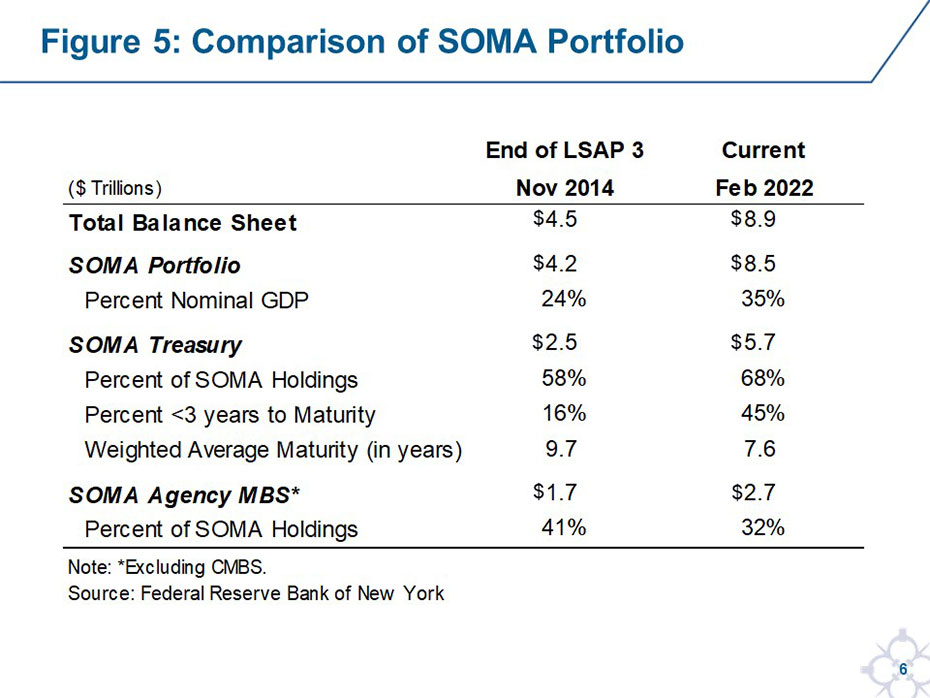

First, the SOMA portfolio is substantially larger than it was at the end of the last round of large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs), reflecting the extraordinary pandemic shock and the purchases needed to support market functioning and the economic recovery. As shown in Figure 5, at about $8.5 trillion and 35 percent of nominal GDP, the SOMA portfolio is roughly double the size in dollar terms and about 10 percentage points higher as a share of GDP than in late 2014. Given the large size of the SOMA, the Committee has suggested that a significant reduction in the balance sheet would likely be appropriate.13 This assessment reflects the view that, with the overall elevated size of the balance sheet, SOMA securities holdings have more room to decline than during the prior period of runoff before reaching levels consistent with efficient and effective implementation in an ample reserves regime.

In addition to the much larger size of the SOMA, the weighted average maturity (WAM) of Treasury holdings is about two years shorter than in late 2014. This is because asset purchases over the past two years have been conducted across the Treasury curve, whereas purchases under previous LSAP programs and the maturity extension program (MEP) targeted longer-dated Treasuries. It also reflects the effect of sales of shorter-dated securities conducted during the MEP.14

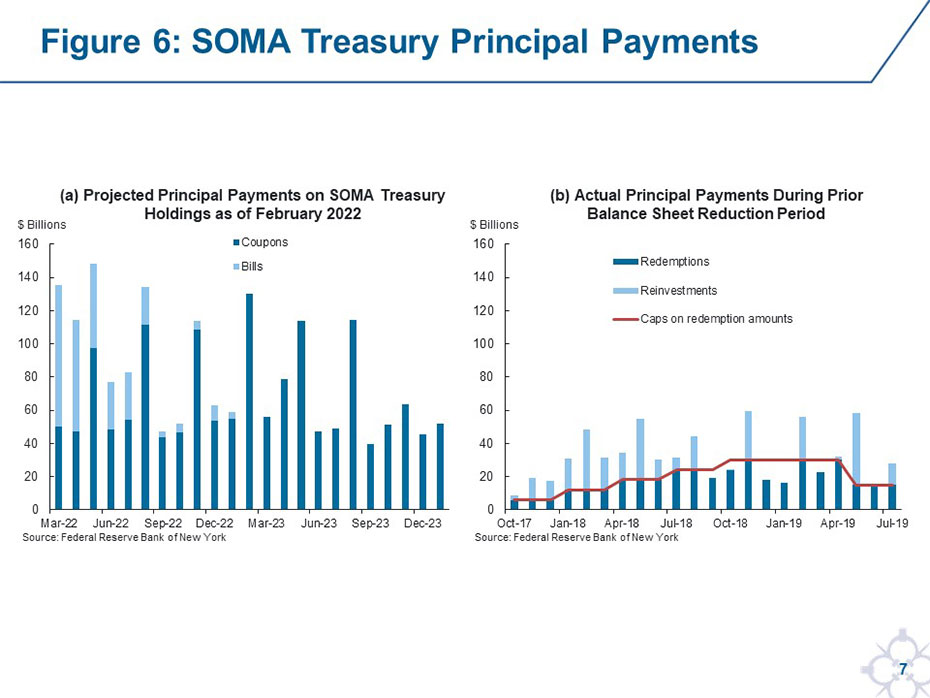

As shown in Figure 6, the portfolio will have sizable principal payments from Treasury holdings over the next few years, ranging from $40 billion to $150 billion per month, and averaging around $80 billion. These could be rolled over or allowed to mature, depending on the Committee’s decisions. During the prior period of balance sheet reduction, shown in Figure 6b, the Committee directed the Desk to phase in a cap for monthly Treasury redemptions of $30 billion per month, to limit the pace and variability of redemption amounts, particularly around the middle month of each quarter when maturities are greater.15 Often, principal payments were below the caps, and the average pace of Treasury redemptions was less than $20 billion per month.

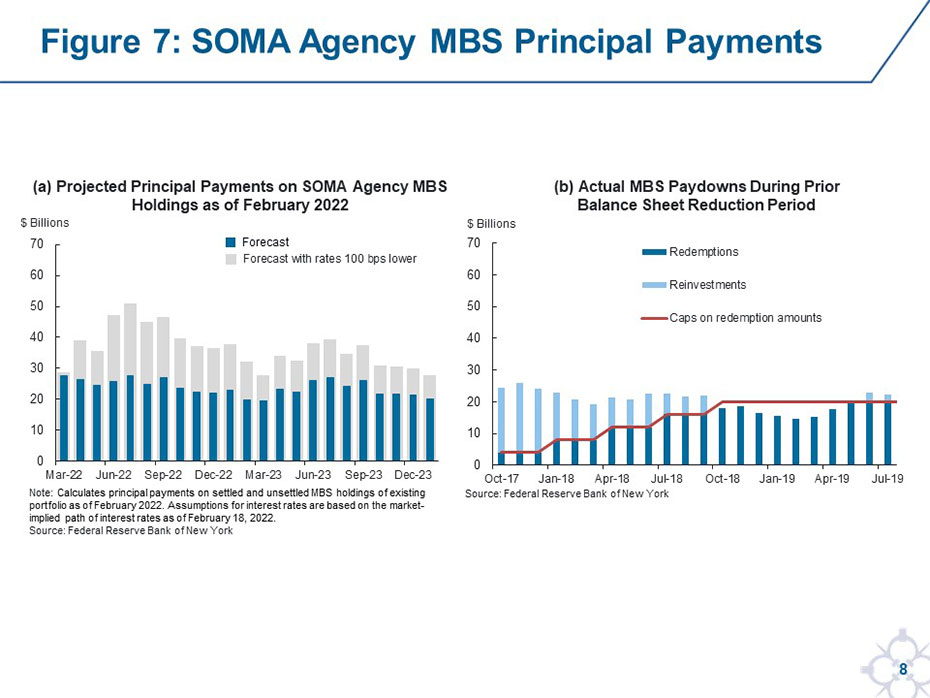

Agency MBS principal payments, shown in Figure 7a, are also expected to be modestly larger than those experienced during the prior runoff period and could average nearly $25 billion per month over the next few years. However, there is considerable uncertainty around mortgage prepayments; a downward shift in mortgage interest rates could increase prepayments substantially, as indicated by the gray bars.16 During the prior reduction period, shown in Figure 7b, the Committee phased in a monthly redemption cap of $20 billion for MBS. This made the decrease in agency MBS holdings more predictable, and also limited the possibility of procyclical reductions in SOMA holdings during periods when interest rates fell in response to a worsening economic outlook. In 2019, as the Committee eased policy, the cap did limit the pace of agency MBS redemptions.

In summary, Treasury principal payments in coming years will be much larger and more variable than they were following the LSAP programs. MBS principal payments will likely be modestly larger and are subject to considerable uncertainty. The FOMC has not decided on its plans for reducing the size of the balance sheet. However, the minutes from the December FOMC meeting noted that many Committee participants judged that monthly caps on redemption amounts could help ensure that the pace of reduction in the SOMA portfolio would be predictable over time.17

Ample Reserves Regime

A second observation is that the Committee’s affirmation of its ample reserves operating framework provides broad insight into the longer-run supply of reserves, a key determinant of the longer-run size of the balance sheet.

During the prior period of balance sheet reduction after the LSAPs, the Committee had not yet decided on its operating framework. Even after the Committee announced the ample reserves regime, heightened uncertainty existed about the underlying demand for reserves given the substantial changes in banks’ liquidity management practices since the Global Financial Crisis.

Today, the operating framework is well established, and we can draw on the prior experience with balance sheet reduction in assessing the demand for reserves. That said, the underlying demand for reserves is still uncertain and varies over time. Most large reserve holders assess their need for reserve balances based on intraday payment flows and projected outflows under stressed market conditions, and each bank has a different profile based on the composition of its liabilities and the outflow assumptions it makes.18 Moreover, the supply of reserves needed to maintain ample conditions is not just the sum of individual banks’ demand, due to frictions that limit the rapid redistribution of reserves.

As the Committee reduces the balance sheet, staff will carefully monitor developments in money markets to understand changes in reserve conditions and inform the Committee's assessment of the appropriate path for the balance sheet in the longer run. Importantly, the prior experience with balance sheet reduction offers a useful guide to money market conditions that reflect ample reserves. The FOMC is committed to maintaining sufficient reserves to ensure that administered rates—the interest on reserve balances (IORB) and overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRP) rates—exercise control over the federal funds rate. However, should pressures in overnight markets unexpectedly emerge, the new Standing Repo Facility (SRF) that the Committee established last year is also available, providing an important backstop to support effective policy implementation and smooth market functioning.

Flexibility in Implementation

As the Committee turns toward reducing the high level of accommodation provided during the pandemic, the Desk will focus on implementing the Committee’s plans as they develop. Overall, the FOMC’s principles provide helpful guidance on the approach to reducing the balance sheet; similar principles communicated in advance of decisions or actions during the prior episode enhanced understanding of the Committee’s approach, supporting effective policy implementation.19 This time around, FOMC participants generally noted that current conditions likely warrant a faster pace of balance sheet runoff than during the previous period.20

Given the experience implementing the last balance sheet reduction, it seems likely that redemptions could proceed smoothly at a somewhat faster pace than before. However, a significant reduction in SOMA holdings will require meaningful adjustments to private-sector balance sheets—as investors absorb the net increase in Treasury and agency MBS issuance and money markets transition to lower levels of liquidity—and these adjustments could take time. And while the Fed has some experience shrinking its balance sheet, this process is still relatively novel. So, the Desk will continue to monitor markets closely to inform the FOMC’s policy deliberations. The Committee is prepared to adjust its approach to reducing the size of the balance sheet, should economic and financial developments warrant.

Potential for Liftoff is Near-Term Focus

Finally, as the principles note, the FOMC will first increase the target range for the federal funds rate before it begins reducing the size of the balance sheet. And, at its January meeting, the Committee stated that it expects it will soon be appropriate to increase the target range. So, I am also focused on liftoff and adjustments in money markets that might occur. Let me offer some concluding thoughts on that.

The Committee last lifted the target range off of the zero lower bound in 2015. At that time, the Fed had no experience lifting short-term interest rates in an environment with abundant reserves, and there was significant uncertainty about the dynamics we’d see in money markets. Ultimately, the policy implementation framework—including the administered rates and associated operations—was very successful in managing the federal funds rate within the target range and lifting the constellation of overnight rates. And as we’ve seen over the past several years, the framework has continued to support effective policy implementation across a range of environments.

Even as the current environment is characterized by higher levels of liquidity than in 2015, I am confident that administered rates will again be effective at lifting the federal funds rate when the Committee increases the target range. Administered rates create strong incentives in overnight markets, and the ON RRP provides a broad range of money market investors an alternative investment to support the federal funds rate and other overnight rates. My sense is that the current setting of administered rates relative to the target range has been working well and that it could continue to support effective policy implementation following any increase in the target range in coming months, although adjustments could be warranted over time.

With the high levels of liquidity in money markets, take-up at the ON RRP facility could increase as rates rise. Flows between bank reserves and ON RRP balances depend, in part, on relative levels of interest rates on bank deposits versus other money market investments, such as money market mutual funds (money funds). Some banks may use rising rates as an opportunity to reduce reserve holdings by shedding deposits.21 If, when the FOMC increases the target range, banks raise deposit rates by less than money funds increase net yields to investors, funds could flow from banks into money funds, which could in turn increase take-up at the ON RRP.

That said, while many expected an increase in the ON RRP in 2015, this did not come to pass, and it could be that ON RRP balances remain relatively steady following liftoff or even decline. Regardless of what happens following liftoff, over time, as the Committee reduces the size of the balance sheet, I expect usage in the ON RRP to decline.

In sum, the administered rates working together should maintain the federal funds rate within the FOMC’s target range. I am confident our tools will promote smooth implementation of the Committee’s policy stance. But as always, we will monitor conditions closely and consider adjustments to our approach as appropriate.