Javier Silva: Welcome to Bank Notes, a podcast by the New York Fed. For this inaugural series, we’re discussing Small Business. I’m your host, Javier Silva.

In this series we’ll share insights and analysis from the New York Fed on a range of small business issues, including credit needs and challenges. We’ll also hear from small business owners about their experiences: the highs, the lows and everything in between. Before continuing, I would like to note that the views expressed in this podcast do not represent those of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

Javier Silva: In today’s episode, we’ll learn about the current state of small business from our own in-house experts. Earlier this year, the Fed published the results of the small business credit survey. To hear more about what it means for small business owners, let’s take a deeper dive into the findings with my colleague, Claire Kramer Mills, Assistant Vice President at the New York Fed. Claire leads the New York Fed’s analytic work on community development issues, with a focus on consumer and small business finances. In 2010 she spearheaded an effort to fill a data gap and gather other intelligence on small business financing, leading to the creation of the Fed’s Small Business Credit Survey, which, today, is a partnership of all 12 Reserve banks and over 400 community organizations.

So welcome, Claire.

Claire Kramer Mills: Hi Javier, it’s great to be here.

Javier Silva: So in this podcast we’re going to learn a little bit about the survey and why the Fed cares. We want to better understand some of the challenges faced by small businesses and also hear some of the takeaways for policymakers. So the survey is a partnership and collaboration among all the 12 Reserve banks, over 10,000 small businesses responded to the survey from about 50 states and the District of Columbia. And this effort has been going on for a couple of years. So Claire, why does the Federal Reserve care about small business?

Claire Kramer Mills: Really, put simply, the Federal Reserve cares about employment. And small businesses employ 50% of private sector workers. They’re really important local employers and of course in the aggregate they’re also a key driver of the economy.

Javier Silva: Why a survey?

Claire Kramer Mills: Following the financial crisis, we, like our counterparts throughout the country engaged in a series of focus groups with local stakeholders. And what we learned in speaking to nonprofit service providers, lenders and other interested parties was that they really lacked local information about small business conditions. And because small businesses are such an important employment channel, we really wanted to get a better sense of what they were saying about their health, about their financing circumstances, and tensions that they were experiencing.

Javier Silva: So the New York Fed has held workshops across our district on small businesses, for small businesses, on how to access capital and I’ve heard the term “small business” used often. What do we mean when we say small business?

Claire Kramer Mills: It is a wide universe. In the broadest sense the Small Business Administration definition of small business is any business that has under 500 employees. Practically speaking, most of the small businesses we hear from in our survey have fewer than 100 and typically have $5 million or less in annual revenues. One important thing to note is that there is a big difference between small businesses that are self employed—don’t have any employees on their payroll—and those that do have at least 1 full-time employee other than the owner. So we distinguish between those two.

Javier Silva: Tell us, what’s happening in the world of small business?

Claire Kramer Mills: Well, the last number of years, following the financial crisis, have been eventful years in the small bus space. It’s been difficult, but we have seen improvement in general business conditions and certainly in availability of financing for small businesses, including some interesting innovations in that space. In the last year that we’ve been tracking changes in small business conditions, we’ve seen pretty steady performance reported from the business owners that take our survey. Very steady demand for financing. We do see some challenges in this space, however, particularly for start-ups, small firms, and minority and women-owned businesses.

Javier Silva: There’s a wealth of data in the survey, which includes information on types of firms and firm size. What’s the difference between these types of firms?

Claire Kramer Mills: So the small business universe is really diverse and one of the things that everyone who looks at this space knows, is there are really profound differences between smaller revenue firms and larger revenue firms. In terms of both credit needs and financing needs and experiences, we see really profound differences between firms that are under $1 million in annual revenue and those that have larger revenues sizes. Typically firms in the sub $1 million space—and these are often firms that are starting up, they’re under five years in existence—they really need small denomination loans or financing vehicles. Most of them are seeking roughly $100K or under in financing. And their outcomes also tend to be different from larger revenue firms.

Javier Silva: And so we hear a lot of talk of where firms access capital. Where did some of these smaller firms pull together their financing?

Claire Kramer Mills: Typically, most small firms and again, here we’re talking $5 million or under, typically from our respondents, most of them are going to traditional channels. You know they tend to have some relationship with typically a bank and are very likely to seek financing through that channel. One of the issues, though is for firms, particularly those with under $1 million in annual revenue, while they make seek financing through a large bank or a community bank that they have an existing relationship with, their success at those institutions really varies and differs from larger firms. There tend to be particularly at large banks, the success rate for small firms is much lower than if they go to a community bank or if they seek credit or financing from another channel like a community bank, or an online lender, or a community development financial institution.

Javier Silva: So one question I often hear from small business owners is about online lending. So I’m glad you mentioned it. This type of lending as you know has come on the scene in the last couple of years. How has this source of credit factored in for small businesses in the survey?

Claire Kramer Mills: Yes, there have been really wide innovations in lending following the financial crisis. And as you note, online marketplace lenders or direct lenders have frankly filled a growing space in the market. They tend to be smaller relative to traditional lenders, main street lenders. But they’re a growing share of the market. And part of that is driven by the fact that they are really speedy in their decision-making which is very attractive to small businesses who may be seeking relatively small denominations, but they need that money quickly in order to provide bridge financing. They’ve got a new contract that they need to fulfill, but they’re not going to get paid immediately for that contract so they need that short-term kind of gap financing. And frankly traditional providers just take too long.

Javier Silva: What are some examples of online lenders?

Claire Kramer Mills: So a couple of the big players that you’ll hear are On-Deck. You’ll also hear Lending Club, PayPal, Working Capital is another provider, and everyone who’s every visited a farmer’s market will know of Square.

Javier Silva: Absolutely. So I’m also interested in learning a little bit more what role personal finance plays in the financing of small businesses. So they’ll go to banks, go to online lending, how about personal finance?

Claire Kramer Mills: It’s a huge, huge factor. So you know when we think about anyone who’s had a good idea or thinks they’ve got a good idea and they want to start a business, they tend to bootstrap, right? They’re going to tap into their personal savings, they’re going to tap into friends and family, and kind of close sources. And that’s very often the early stage capital that you use to start a firm. In terms of when a firm gets to a stage of development where they need really to seek money outside of their own personal pockets, they’re going to rely on their personal credit score in order to apply for financing from a bank or another channel. Very often if they’re applying for a loan or a line of credit product, you know, there’s a need to pledge collateral to secure financing. And what we see in our data is that even firms at later stages of maturity and of greater size are still using personal assets as collateral to secure their financing.

Javier Silva: That is quite an interesting point. And so if I understand it correctly, the personal credit and the business credit are one in the same in the early stages of a small business?

Claire Kramer Mills: In the early stages, and even later stages of development—at least as far as collateral is concerned—personal assets still are very, very commonly pledged. In terms of personal credit score vs. business credit score, there are differences as firms mature and grow there tends to be a greater use of business credit, but personal credit is still thrown into the mix.

Javier Silva: And what’s the average amount of borrowing for a small business, for these younger businesses?

Claire Kramer Mills: Yes, for younger businesses in earlier stage and smaller, you know, those things are related. We’re really talking in most cases, $100K or less in credit. The overwhelming majority are $250k or less. And increasingly, you know, that’s a market that’s not super profitable for traditional lenders, and it’s often because newer firms and younger firms don’t have an established track records. It’s a tight lending space for them, you know, which again underscores the attractiveness of alternative providers of capital.

Javier Silva: So once a small business owner has all of their financing together, how are they spending this capital? Where are they deploying it?

Claire Kramer Mills: Well, you know, that’s a question about why firms are seeking capital is a great one. It’s one that we’ve been tracking basically you know since we came out of the recession. And what we’ve seen is an evolution, frankly. The majority of firms coming out of the financial crisis were really seeking working capital. They just needed to kind of keep the lights on and keep operations moving. But now we see that the majority are seeking capital to grow their businesses. It’s because they’ve got new contracts that they want to fulfil and they need either bridge financing or they need the financing to secure and take advantage of a new opportunity.

Javier Silva: In the survey 35% of businesses were either female-owned or had equal ownership and we know Hispanic-owned firms are also rising. What else about small businesses do we need to understand?

Claire Kramer Mills: Well, I think one thing that’s really important to understand that there are profound demographic changes happening in the small business universe. And that has really important and notable implications for employment for America in the future. So 30% of new businesses are owned and operated by immigrants. As of 2016, according to Kaufman information, 24% of new businesses are owned and operated by Latinos. Those are really interesting numbers on the face of it. But when you start to look and unpack, and think about the potential of these firms, one thing we know is that Latino owned businesses are not really scaling to the degree that we might think. And by scaling I mean growing to revenue sizes of $1 million or over. Only 2% of Latino-owned businesses have grown to, in excess of $1 million in annual revenues. To connect this back to the original question of employment, the significance of 24% of new businesses being Latino-owned is really important because if these businesses are unable to secure sufficient capital or are unable to grow, that will have important and negative employment implications for the economy.

Javier Silva: So as these businesses—and all businesses, really—pull together their financing together, there’s a great need for technical assistance. So where can a firm owner go to seek help?

Claire Kramer Mills: There are a lot of local and national networks that provide counseling and frankly free advice to small businesses. One of them best known is Small Business Development Centers which are typically housed at colleges and universities, and they can offer advice and guidance on everything from an idea that has not yet been developed into a formal business, to formulating a business plan and beyond. There are also networks like SCORE, which is a network of retired professionals who provide technical assistance to small businesses.

Javier Silva: And so do community development finance institutions also provide technical assistance?

Claire Kramer Mills: They do. And what’s really novel about community development finance institutions is that they marry guidance with provision of capital. And, CDFIs as they’re commonly known, are able to take a little bit more risk than traditional lenders on their portfolios, so that enables them to tap into part of the market and to serve part of the market that might not qualify at the moment, you know, for credit at the best terms and at the best rates. What we know from our survey, is that though they typically are a small part of the market, they are very good at serving segments that have typically been disenfranchised or left out of the credit market and that the borrowers who work with the CDFIs are tremendously satisfied.

Javier Silva: And so the next step from a CDFI would be a traditional lender?

Claire Kramer Mills: The goal from a CDFI, and frankly from a broad set of players who are now operating in the market, some for a profit, is to really help firms establish a credit track record, a credit history, a reputation, that will enable them to enter the mainstream to seek, as they grow, to seek larger sums of capital for their business, and to obtain capital at the best rates and the best terms.

Javier Silva: And that’s great for communities.

Claire Kramer Mills: It is.

Javier Silva: Claire, I want to follow up on Latino-owned firms. What’s holding them back?

Claire Kramer Mills: That’s a great and pressing question. So, to date, very few Latino businesses, its 2%, have scaled to $1 million or greater in annual revenues. One of the big challenges, of course, is securing capital. Many are not, don’t have enough of a track record, or enough of a history, or a sufficiently high credit score to qualify for traditional capital, and that means that if they’re securing capital they’re doing so at higher rates, which can definitely slow down their expansion. Another, of course, important issue that is tied to capital access is access to procurement opportunities. And really scaling through contracts with major major corporations and large entities like hospitals and the education sector. To date, Latino performance and access to those networks has not been what we would expect.

Javier Silva: So it seems that not only Latino-owned firms, but just firms across the board, are having difficulty accessing capital. And it looks like, from the research, more small business owners are heading to online lenders, and alternative lenders, and other lenders. Why do you think that is?

Claire Kramer Mills: Well, over time what our data have told and us, have indicated, and I think a lot of providers—increasingly new providers instinctively knew—was that the bulk of small businesses are not being well served through traditional channels. And you know, that slows down their growth, and for firms that have not as much of a track record, or don’t have pristine credit, they don’t have a score of 720—they’re going to seek credit through other means. And online lenders have really perfected, or increasingly perfected ease of applying. You can easily upload your documents. You get a decision really quickly. The money is in your bank account in rapid fire. That’s very, very different from traditional lenders.

Javier Silva: So what issues would you raise for policymakers?

Claire Kramer Mills: Well, I think that the online lending space is a new space. It’s evolved quickly and the framework for regulation and transparency has not kind of caught up to speed with where the market is now. The other thing I would point out to folks, policymakers, who are starting to look at this is, the really big difference between the propensity of smaller firms and perhaps less sophisticated firms to seek credit through these channels is much, much higher than larger and more mature firms. And given some questions about transparency and understanding about what those loans really mean practically, I think that is an important issue that we have to tackle.

Javier Silva: So firms on the smaller side are going to these non-banks, or non-main street type of lenders. And CDFIs (Community Development Financial Institutions) and credit unions are picking up some of the slack. But not all of it?

Claire Kramer Mills: That’s right, in terms of scale CDFIs are a venerable channel, but they’re relatively small in the marketplace.

Javier Silva: Well Claire, we heard a lot today and there’s so much more to talk about. Thank you for joining us. This has been a very informative conversation.

Claire Kramer Mills: Thanks so much Javier.

Javier Silva: That wraps up today’s discussion on small business. In future episodes we’ll talk to a variety of small business owners on how they built their businesses. And they’ll provide some practical advice from their own lessons learned.

Javier Silva: Welcome to Bank Notes, a podcast by the New York Fed. For this inaugural series, we’re discussing Small Business. I’m your host, Javier Silva.

In this series we’ll share insights and analysis from the New York Fed on a range of small business issues, including credit needs and challenges. We’ll also hear from small business owners about their experiences: the highs, the lows and everything in between. Before continuing, I would like to note that the views expressed in this podcast do not represent those of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

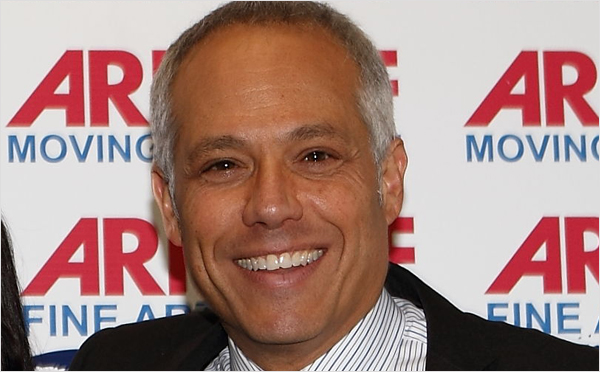

When you grow up in a family business, there’s more than just profits motivating you to succeed. It’s family history. A legacy of service. And the future of your family. Today, we speak to the third generation owner of a business that started in the 1920’s with a single truck. Mike Arnoff was "born" into the moving and storage business, and by the age of 15, he worked summers and part-time in his parents’ company—but that was just the beginning. Today, he’s President of Arnoff Moving and Storage.

Welcome, thank you for joining us.

Michael Arnoff: Good morning.

Javier Silva: So let's get into a little bit about your company. We want talk about the origin story, the evolution through time, and get to bring us up to the present day, and talk a little bit about the future. So, Arnoff Moving was started by your grandfather in the 1920s, in Lakeville, Connecticut, which is in the northwest corner of Connecticut. Share with us the story behind how that company started.

Michael Arnoff: So, you know, Louis was an industrious type of guy, and he was sort of the guy around town that could get odd jobs done. So he had a truck, and, you know, if you needed your basement cleaned out or if you needed something moved, he was sort of the guy to go to. And the interesting thing about the community of Lakeville and Salisbury, the town of Salisbury in Litchfield County in the northwest corner, is a lot of New York City families, wealthy families, had homes there, weekend homes, summer homes, whatever it might've been at the time. And Louis became the go-to guy, where, as people were traveling in Europe and going on these extensive trips and buying antiques and items for their home, or adding to their collections, they would call Louis, and say, ‘hey Louis, next week the ship's going to be in down at the pier in New York; can you go down and pick up the cases of all the items that we purchased on the last trip?’ So, in short order, a moving company was established based on the fact that Louis realized he had some capabilities, and he certainly needed to work—he was a young guy and starting to think about having a family—and he went to his stepdad Abraham, and Abraham helped him, loaned him some money, and they established, in 1924, the first truck.

Javier Silva: From our Small Business Credit Survey, we know that many new small businesses don’t typically make it past the first two years. How did it work out for your grandfather? Did he seek additional financial sources?

Michael Arnoff: The local bank in Lakeville, still there today, is called, the Salisbury Bank and Trust Company, and you know, as the story goes, Louis, was, he understood borrowing, so he was working in a business where you made some money on Monday and you spent it on Tuesday and you made some money on Wednesday and you spent it on Thursday. So it's not like he ever had that much money, but he knew that if he needed money, he could go to the local branch of the bank and borrow $25, and which, of course, at that time, was a fair amount of money, and over the next few weeks pay it off $5 at a time. So, as we look back on the family, he was a real borrower. He really understood that. And, um to this day, five generations later, our family still banks with that small bank in Lakeville, Connecticut. They've now of course spread out, and they're more of a community bank, located in three states—Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York—and it's still called the Salisbury Bank and Trust Company.

Javier Silva: So, the company grew, you found success. What was the company's big break after that?

Michael Arnoff: In 1948, I think probably one of the first real breaks came along, where a national company called North American Van Lines needed an agent in the northwest corner of Connecticut to help service moves. And at that time, Van Lines, which were formed in the middle to late ’30s, were really back-haul agents. So if you move somebody to Chicago from Connecticut, you wanted something on your truck to go back to Connecticut with, it was a place that you could send a telegram to, and say, “Hey, next week, I'm going to have a truck empty in Chicago; do any of your agents have any loads that are going back to New England?” And so, lo and behold this partnership was very good for Louis, and it helped him really build his company, and he became an agent for North American Van Lines, and this year, we'll actually celebrate our 60th year in a relationship with that organization, and we're pretty proud of that long-term relationship.

Javier Silva: So that takes you from being a very small company in northwestern Connecticut to being more of a regional player, and then now, more having more of a national presence with this partnership.

Michael Arnoff: Well, I think that partnership gave him a larger wingspan. It gave him the ability to open up new business opportunities that he wasn't able to service prior to that time.

Javier Silva: Take us through now the ’70s and ’80s and that progression, and then particularly when you joined the company as well.

Michael Arnoff: My dad, Richard, the third generation, joined the company in approximately 1960, and the company was still operating out of its location in Lakeville, Connecticut. At that time, IBM was operating in Poughkeepsie, and they were starting to develop a factory in Fishkill, New York, a town south of Poughkeepsie. And, my dad went and started to market his capabilities for handling sensitive shipments—private collections of art, antiques—to this company that was, you know, a major up-and-coming, growing, massive company, and he was able to close sales. So, within the next 10-year period, he opened a large facility in Poughkeepsie to be able to service their needs, to have a terminal close by their facility, and to have a warehouse to be able to provide storage services for the equipment and items needed in their manufacturing process. So our company still maintained its capabilities of moving families, which we still do today, but he started to diversify in moving equipment, raw materials, and manufacturing machinery.

Javier Silva: When did you join the business? And what was your focus following the expansion of the company to Poughkeepsie and working with IBM?

Michael Arnoff: I decided to join the company in 1984 and really two things were going on at that time. And from a marketing background, my ideas were business development, and we started to look north toward Albany and what was going on in the capital of the state. I'd always realized that the state capitals were very stable economies, and we wanted to have a presence with that stability and start to further develop our office-moving capabilities that had been developed through the ’80s. Also, simultaneously at that time, a lot was going on. There was a lot of development around the Stewart Airport area in Orange County, New York, just outside of Newburgh. So, two things went on over the next couple-of-year period. One is that we opened a warehouse and operation in Albany, in downtown Albany, and the next thing that happened was that we bought our largest competitor in the lower Hudson Valley, out of Newburgh, and took over his operation and developed a further operation in Orange County; with it in mind that this airport was going to develop and there was going to be a lot of opportunities for us potentially at that airport with moving freight and baggage handling, or whatever the case might be.

Javier Silva: So as you took advantage of other opportunities in the region, were you still working with IBM? And, if so, how was that business line developing?

Michael Arnoff: In the early ’80s at that Fishkill site at IBM, they were developing semiconductor chips. The first time I experienced the concept of a clean room was probably around 1985, and equipment was being moved in and out of a clean room, and it's very, very sensitive. The equipment was sensitive, but the environment that you're working in was very, very sensitive. So I started to realize that this was a niche that not a lot of movers, millwrights, or riggers had the ability to do. Movers could move things, millwrights could rig things, but none of them had really experienced, working specifically in a clean-room environment. So I realized that that was potentially an opportunity for us to specialize and differentiate ourselves from our competition.

Javier Silva: Tell me more about diversification into different business lines. How did that set you apart from your competition?

Michael Arnoff: So continuing to develop our company and diversify our company, one of the things that Louis—going back to Louis's days—he moved a lot artwork. He had built relationships with the New York City auction houses, and he had private collectors, and he had this expertise of being able to move sensitive shipments. So we started a marketing campaign in the late ’80s to the New York City art community telling Louis' story, and telling our story that here we took what Louis was capable of doing, and Richard took that to sensitive equipment, and we still have these two real strong capabilities, and customers in the metropolitan Boston—Washington, D.C. corridor started to realize that we could service their transportation, storage, and crating requirements.

Javier Silva: What’s your company’s philosophy?

Michael Arnoff: What Dad always taught us was, whether you're moving China, or packing China that somebody bought at Tiffany's, or whether they bought it at Woolworth's, it's their possessions, treat them the same, it doesn't matter where they were purchased. We take that sensitivity today, we treat everything as sensitive, because we don't know to you whether that dish or that piece of equipment has a different level of sensitivity than the one next to it. So maybe it was your great-grandmother’s, and maybe it means something, it has some level sensitivity to you, and maybe it's a Rembrandt, and maybe it is worth a few million dollars. But if we put the same level of sensitivity to everything that we move, it's the success of the end result.

Javier Silva: In the New York Fed’s Small Business Credit Survey, banks—particularly small banks and credit unions—are a key source of financing. Can you describe your relationship with your bank?

Michael Arnoff: So our banking relationship is always very important. And when I say important, it almost becomes more than just a professional relationship; it needs to be a professional level of intimacy where the bank has an ability to understand what we're doing, because we're in such a specialized industry. What we found is that some bankers really don't understand what we do, so it's our job, the same way we educate a customer about what we do when we're talking to a new customer, we need to educate the banker so that they understand why we need to go buy that particular trailer that's custom built for us and why we just can't go to a lot and buy just a trailer off the lot. The custom-built trailer's twice as much as just the regular trailer that you see going down the road. So my goal has always been to try to educate the banker so that he really understands. Of course, he's being educated by our CFO with our financial information, but I think it's important in building the relationship with the banker that the banker really, truly knows who we are. I, more than twice a year, invite our bankers into our facilities, to different facilities, take them on a tour, show them what we're doing, whether I take them to the crating shop, and they actually see that. And I find that these guys love it. I mean, they love getting out from behind the desk, right? Sometimes they want to roll up their sleeves and cut a piece of wood, but I think it's important for them, because we're not, you can't open up a book and get a rating on who we are. We're not just the typical manufacturer. We're not just a typical trucking company. So it takes time for them to understand who we are. And that can be a hindrance sometimes because I just can't go into any bank and get a loan; I need a relationship with my bank.

Javier Silva: So shifting gears for a moment, what were some of the challenges you faced over the years? For example, how did something like 9/11 affect your business?

Michael Arnoff: We have what we call our base business, our residential family moves, and then we have our logistics business, which is basically our business to business. It's machinery, it's office moving, it's warehousing and distribution services. So 9/11 hits, and basically within a day or two, the logistics business comes to a screeching halt. People aren't buying equipment, people aren't allowing artwork to be transported, the insurance companies are putting a halt on art exhibitions. Over the course of the next year, government funding for art exhibitions was pulled back. So that whole, for about a year or two, period of time, that business really slowed way down. Companies weren't buying machinery. It was a scary time. People who needed to move were still moving, so some of our business focus was shifted to the residential. We certainly had a fair amount of people moving out of New York City, so we had some level benefit there, and we could shift some of our assets and some of our drivers and helpers and some of our talent, our labor assets, into the residential moving business, so that became the mainstay of the company, and because of that diversification, it became a success driver for us.

Javier Silva: What came after that? Can you tell me about other challenges you’ve had along the way?

Michael Arnoff: So, we plug along after 9/11. By 2003, 2004, the logistics business is starting to pick up steam again. The housing market by 2005 is a record-breaking year for us with residential moves. By 2008, the housing crash affects us dramatically by that part of our business—that business unit—coming to a screeching halt. So previously, we withstood the pressures of our logistics business coming to a screeching halt. If houses aren't selling, people aren't moving. It's just plain and simple. So now, here we are a few years later, fresh in our mind from 9/11, and we're going through another dramatic down in one of our business units. So here, we did just the opposite. We started to shift talent and trucks and staff from one business unit to another business unit. We put a lot of emphasis, marketing emphasis, in 2009, in 2010, on the semiconductor industry, on the industry that transfers art, on special products, on warehousing services. And we really focused our marketing attention away from the residential and family moves to the logistics business.

Javier Silva: As your residential business was slowing down as a result of the financial crisis, what was your financial strategy to get through that period?

Michael Arnoff: As a business owner and certainly one of the things that may have kept me up at night during that period of time was how are we going be responsible for our debt? So, when one part of your business—at least one part of our business, when I'd look at our diversified business units—starts to falter because of the market, we have to shift gears pretty fast. And at that time, we set up a bit of a war room in our office, we got our marketing team in place, and we said, okay guys, this is not now a long-term, this is not what's going to happen next year or what's going to happen three years from now in a marketing plan; this is, we need to shift gears today for tomorrow. And we have employees, long-time employees, that are expecting to come to work tomorrow, and we have truck payments that are going to be due in 25 days, or whatever the case might be.

So we need to take those assets, and again, Javier, we look at our trucks, right, our equipment as assets. We look at our drivers and helpers and employees as major assets of our company. Our warehouses also, those are our three primary assets—how can we deploy our warehouses and our labor, our drivers and our helpers and our equipment to shift gears, right?

So if at that time, when the housing market crashed, and we had crews that were predominantly moving families, can we take them and shift them to doing equipment relocations? Can we give them a high-speed training over the weekend, to be able to understand and shift gears? Now listen, not every employee wants to do that, right? But then it's up to the employee to decide that here's what the company's going to do, let's be open and frank, let's communicate to the employees, which is what we did. We had a company-wide meeting, I stood in front of them, I promised that no one was going to lose their jobs as long as they were open-minded and were willing to shift gears with us, and I'll tell you it was success. It was hard. It was hard for all of us. But I think it's the way it was communicated.

You know, I look back on it, and someone sometimes says to, you know, after 30 years in a job, what's your biggest success? Well, maybe that's probably one of my biggest successes is that we were able to maneuver out of that housing crisis, and shift gears, and today we look back on it and it's a blip in the road. And for Arnoff we came through it, and you know what? We're better for it. And we proved to employees that they could shift gears, and, you know, you have long-time employees that do the same thing every day, and they don't realize that they have talent to do something else. So in the long run, it made us better.

Javier Silva: I want to circle back to your workforce. What is your approach to your workforce and staffing your business?

Michael Arnoff: So, Arnoff has a significant family culture. We're a family business, five generations. We really put a lot of emphasis on training. We've always hired young men and women. Sometimes it's their first job, sometimes that's summer help. You know, they might be a college student, so it might be their first summer job. So we have experience in working with a younger workforce. But most recently we found a great success in hiring veterans. Fifteen percent of our workforce today are veterans, in all areas of our company, from management, right on down to entry-level. Last year we were awarded by the American Legion, New York State's Employer of the Year. We're very, very proud of that. Because of the training that we do, because of the benefits that we offer veterans, in some cases we've made some exceptions and accelerated the benefits for those that need it, you know, as a family business, we can shift gears pretty quickly, so we can help when needed. And the veteran workforce is a workforce that sometimes needs that little added care and concern. I think what's important is, we have a saying at Arnoff, "Suit up and show up." Veterans know how to suit up and show up. And what I mean by that is, not only put your uniform on when you come to work every day, but come with the right attitude, and come to work, and be ready to execute. We're in a service business. We're not sitting necessarily in front of a machine, pounding out some specific part. We're in front of a customer all the time. We're out in the field. So we need employees that can embrace a customer, understand customer service.

Javier Silva: So about 15% of your employees are veterans. In terms of the rest of the workforce, how much training do you do? Walk us through the other 85%.

Michael Arnoff: Okay, so sometimes we get a guy with a CDL-A. He's got 500,000 miles under his belt, and he's looking for a new job. So that's great. Maybe the training that he gets is a little different than someone that comes in as a driver’s helper and says, “Someday I'd like to be a driver,” right? So we do have a mentorship program where someone like that can be mentored by a senior driver. The senior driver gets additional compensation for being a mentor, so he gets some remuneration for that, but he also gets some accommodation from the company and in his success at the company. Drivers and helpers are an important part of our business, but we also hire a lot of administrative staff to help run our company, whether that's in the financial team, whether that's in our customer service team, or whether that’s in our sales and marketing team. So we hire people that don't necessarily know. We could bring in a salesperson that has sales ability, but they don't know anything about logistics or they don't know anything about, they've never moved before. So we provide training in those areas, whether it's a webinar or whether it's some type of industry training that we can latch onto from one of our trade associations, or you know we have had success with local community colleges, in the Hudson Valley specifically, in the northern Hudson Valley, both at Adirondack and Hudson Valley Community, or in the lower Hudson Valley, at Dutchess Community. Through the SUNY system, we've had some very good success.

Javier Silva: I'm glad you mentioned that because the workforce development is a huge issue, particularly in the middle skill-jobs sector, which is where I think a lot of your employees fit in...

Michael Arnoff: Most, right.

Javier Silva: And these are really great-paying jobs, so it's a nice pathway for folks, particularly who do not have a four-year college degree and are looking for a solid job, I think going through this path is actually beneficial.

Michael Arnoff: You know, and we promote from within. I mean, I know it's hard when somebody leaves a particular position because now you have got to fill that position, but what's it all about? It's about helping people have a better life, right? If making more salary is what's needed or maybe it's a better job or maybe they do have interest in being a bookkeeper and we can send them in the evening to a bookkeeping class at the community college, isn't that better for them, and isn't it better for us? So that's been the culture and the strategy.

Javier Silva: From our research on Small Businesses, we know they’re a big driver of job creation. And it’s clear from talking to you today that family business, in particular, is important to you. How do you do relate to other small business owners? What do you do to help them?

Michael Arnoff: So I think, to some respects, when you ask me that question, it's more of a personal question than, so maybe I take off my president’s hat of Arnoff Moving and Storage, and sort of answer as Mike Arnoff. I feel it’s a responsibility to give back to the community, not necessarily defining what the community is, you know. But I think my passion is more to try to talk to people that are in family businesses. I’m very intrigued with how family businesses develop. I'm very proud of our family business. I like to tell our story. I hope that by meeting with other family business owners, and especially maybe the younger generation that's thinking about getting into the family business and they're scared or they don't know what to expect, maybe there's an ability for me to help them share my successes. And a lot of it is the simple word “communication,” how I communicate with the fifth generation. At this point in my career, I'm really the coach; I'm really the mentor. I have three leading managers that are in the fifth generation that have joined our company. They’re working side by side with managers who I hired 20, 30 years ago. Our vice president of sales, I hired, I think he's in his 34th year. He's one of the first people I hired when I came back to the company. So he's working side by side with my son. There's integration there, so it's not necessarily he's working with me every day, although we work at the same company, but he's working with another senior manager, and how's that relationship working? So if I can share those successes with someone else and give back, I feel an obligation to do that. I mean, we've had a lot of successes. We've grown our company significantly. We're excited about that. We're excited that the future looks very positive, especially with what's going on in the economy right now. All of that is going to help us. Manufacturers are going to buy more equipment. I believe with pent-up demand in the Northeast to buy a new house or to improve the house that you're in, with the capability to borrow money, it's only going to benefit every one of the diverse business units that we operate in to help us grow our company even further.

Javier Silva: So, you've built your company on diversification, going into different areas, right? But you have one common theme. I mean, you have your warehouse, you have your workers, you have your trucks. In terms of opportunities and challenges, what are you thinking in terms of the next couple of years? What do you see as an opportunity for your company?

Michael Arnoff: One of the newest services that we provide, business units that we have, is a delivery service what we call Final Mile Delivery Service, where companies that sell products, primarily large products online, need someone to deliver them from a particular warehouse to the end user. So what we do is we work with manufacturers who, let's say, make mattresses, and they deliver in a truckload of mattresses to us that are sold online and now need to be delivered in a, let's say, a 200-, or 300-, or 400-mile radius of our warehouse facility. So, we provide a service to deliver those mattresses. And it could be pool tables, it could be kitchen cabinets, it could be windows and doors, things that maybe you traditionally went to a store to buy, and now with the advent of the Internet and Amazon and all the different channels that we have, that model’s changing. So we built a network of delivery service throughout New England to be able to service this business. And I envision that that's going to continue to expand and expand, and I'm hoping that the investments that we're presently making in that business is cutting edge, and it's going to potentially change a part of our company significantly in the next two to three years.

But again, going back to our banker, right? So, I have to take our banker through that facility and through that process and that thought pattern for him to understand what it is that we're doing, because if he looks at it on paper, sitting at his desk back at the office, he just sees that Mike needs 10 trucks, and he's got 10 drivers and 10 helpers going out in this scheduled delivery, and to him it's a trucking service. But it's not just a trucking service. It's a specialized business unit that's going after a major change and a trend of how people are buying things. So it's my goal to teach him that so that he understands that when I need to buy five more trucks, he understands what the business model is that's going to be able to afford to pay the debt.

Javier Silva: So it's the online retailing meeting the bricks and mortar of the transportation?

Michael Arnoff: Exactly.

Javier Silva: Well, Mike, clearly you have a passion for your employees, for your family, for your business. We wish you the best of luck now and going forward with all that you do. Thank you for joining us here today. We appreciate your time.

Michael Arnoff: This was a lot of fun. I really appreciate it.

Javier Silva: Welcome to Bank Notes, a podcast by the New York Fed. For this inaugural series, we’re discussing Small Business. I’m your host, Javier Silva.

In this series we’ll share insights and analysis from the New York Fed on a range of small business issues, including credit needs and challenges. We’ll also hear from small business owners about their experiences: the highs, the lows and everything in between. Before continuing, I would like to note that the views expressed in this podcast do not represent those of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

With the rise of companies like Uber and Airbnb, you’ve probably heard of the gig economy. But gig workers aren’t the only ones on temporary assignments. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 5.9 million contingent workers in the U.S. in the spring of 2017. And to connect those workers with the companies and governments that employ them, there are businesses like the one co-founded by our guest today.

Ranjini Poddar is the CEO of the staffing firm Artech Information Systems. Back in 1992, while she was working her way through law school, she co-founded Artech with her husband who had just earned his MBA. Artech is now a $450 million company and the 11th largest IT staffing company in the U.S., with more than 30 offices. How did it get there? Ranjini takes us through how Artech went from a small business to a successful company with more than 7,000 employees around the globe.

In today’s episode, my colleague Brian Manning serves as moderator for a conversation with Ranjini.

Brian Manning: Ranjini, thank you for joining me today.

Ranjini Poddar: My pleasure. Nice to be here.

Brian Manning: Well, there’s going to be plenty to talk about, as far as your firm goes, but before we get there, I just want to ask you a little bit about your background, if you could tell us how you came to start and run your own business.

Ranjini Poddar: Sure. So I immigrated to the U.S. with my parents when I was 8 years old, and my dad had his own small business when I was growing up. And, he had founded it shortly after we arrived. And when I was very young, I mean, probably 11 or 12 years old, I used to help him out with all matter of things. And I still have this vivid memory of doing analysis on a VisiCalc spreadsheet on an Apple computer, all very extinct products now, when I was about 12 or 13. And really kind of worked with him summers in high school and so forth, and I grew up around a business. It teaches you the components of having a business and things that you think about. And I think I always kind of had that mindset. So essentially what happened is I went to college, ended up in law school. My husband was doing his MBA, and when he graduated we were kind of debating. He had prior to go doing his MBA, he had worked in the IT field as a consultant.

Brian Manning: Okay.

Ranjini Poddar: And so he knew of the industry. And when he graduated, we were debating whether he should go look for a job or we should start a business. And we kind of decided to take the plunge and start Artech at that time. So I was a full-time student, and he had just graduated. So I would help him with everything other than doing the sales and marketing aspects, you know, anything I could do sort of on a part-time basis.

Brian Manning: Okay.

Ranjini Poddar: That's how we started out.

Brian Manning: I know from your biography that you have a background in law. Why did you decide to switch from law to into IT staffing?

Ranjini Poddar: I think going to law school was a little bit of a tangent for me. I applied to law school, and I was fortunate enough to get into Yale. So I ended up going to law school and worked for a large law firm on Wall Street, doing corporate law, doing M&A and securities work and everything else that a large corporate law firm does. And I really enjoyed it. However, five years in, I had two children, a commute, was trying to work the number of hours that were required to be worked at a firm like that, and really didn't have a path to making partner. And Artech at that point was at an inflection point. My husband had basically been running it, and we had grown but not enough. We were in danger of kind of being left behind.

We were a little too small to be competitive in our industry, and so we had engaged a consulting firm to help us in terms of strategy. They had prepared a two-day retreat, and they wanted me to join because they knew I had been involved and give my thoughts in terms of how we could grow. At dinner one day, the leader of the firm turned to me and said, “Well, why don't you join Artech? I mean, this looks like something that you would really excel at.” And I had never really seriously thought about that before. I mean, there are a lot of reasons not to, including working with your husband on a full-time basis and leaving a legal career that you've trained for three years and worked in for five years, and while I had a very pedigreed background, once you step out of it, then it's very hard to get back into it. So I really thought about it long and hard and ultimately decided to make the jump and do it. And I guess it's one of the best decisions I've made in my life.

Brian Manning: Why don't you tell me about Artech? What is the firm? What are some examples of things that you do?

Ranjini Poddar: Artech is a workforce-solutions company. We operate in a few different areas. The primary one is we do onsite consulting primarily in the IT area but also a bit of engineering and other types of professional skills. And what that basically means is a lot of our clients are Fortune 500 companies or government organizations that have contingent staff that rounds out their workforce. So anywhere from two to 10 percent, typically, of their workforce may be contingent as opposed to being full-time employees. And in the IT area in particular, we find that talent that meets our clients’ needs and employ them and deploy them to the client’s site.

Brian Manning: And are these mostly temporary positions, or do you end up placing people for the longer term or permanently, ever?

Ranjini Poddar: So, it tends to be a mix. I mean, we specialize in contract work, so typically they're working at our client’s site anywhere from, you know, six months to a year, often longer. It just depends on the client's needs. So it could be as long as two or three years. Sometimes the client will hire them as full-time employees if they have a need and they have a headcount availability and they like the work that the staff member is doing. And sometimes it's just straight contract work, and the person finishes that project out and goes on to the next one.

Brian Manning: I'd like to know a little bit more about your business model and how the company is structured. You're going to have your own employees who work for the firm, and then you're going to have the contract employees that you're placing with clients.

Ranjini Poddar: Essentially, our employee base is split into a couple of different components. So we have what we refer to as our corporate employees, which is basically our internal staff, and they can be management/support functions such as accounting, HR, IT; or our core functions, which are really sales and recruiting. So that's one component of our employee base. And then the second much larger component is our billable staff, and that's the talent that we are typically employing on a contract basis. So we are the employer of record, but we are typically just employing them for the duration of the contract. And they are deployed out to our clients’ sites.

Brian Manning: Okay. So, you specialize in IT, and that's going to be something that would apply across industry groups. What different types of industries are you providing workers for?

Ranjini Poddar: The major users of contingent staff tend to be in a few different industries: telecom, financial services, sort of high-tech engineering type of companies, government organizations, pharmaceutical firms. Really, it's across the board. And so we have about 70 Fortune 500 companies that are our clients, and then an additional 50 or so that we're actively engaged with that are not necessarily Fortune 500.

Brian Manning: Are there particular skill sets that are in demand right now?

Ranjini Poddar: The technology is constantly changing, so I think what you would typically think of, such as mobile app development, data analytics, big-data type of skills. Java is perennially in demand. There's always a shortage of really talented App Dev folks. So it really runs a broad spectrum. I think the demand ebbs and flows depending on the industry and the location.

Brian Manning: So, to come back to your workforce for just a minute, can you tell me about how you go about identifying, recruiting, and possibly training the workers that you're going to be placing with your clients?

Ranjini Poddar: As far as the staff that we place at client sites, it falls into several different buckets. Typically our clients are looking for—they're typically paying premium pricing for—someone who's going to come in and be ready to go on day one and finish a deliverable in six months to a year.

However, there are certain positions, more junior positions, where our clients may be looking for folks that can be developed. So we are often looking for college graduates or working with colleges in terms of their outplacement offices and trying to identify that talent. Again, because we're in the contingent workforce business and we're employing these folks for a defined time period, the training really depends on the nature of the contract.

Brian Manning: Tell me a little about your approach to running Artech. How do you think about the services that you provide?

Ranjini Poddar: My personal philosophy has always been client first, and whenever I make a decision in terms of how I'm running the business or what I'm doing with Artech, then I'm always thinking about how does this service the client, and how does this help us meet our client needs? And I think that sort of philosophy has helped us structure ourselves to deliver first to the client and really build long-term partnerships with them and not take a short-term approach. And as a result of that, we have focused on building dedicated teams for our enterprise customers, which has really allowed us to get to know our customers and their needs and provide the right talent to them in the right amount of time.

Brian Manning: To build those effective teams, how do you find and manage the talent that you recruit for clients?

Ranjini Poddar: We have collected a huge candidate database over a period of many years. So I think we have about 12 million unique candidates in our database right now. And over a period of time, we've qualified a lot of folks with the technical skill sets and also have built a database of their experience. If we have deployed them on one project, they've come off, and then we’ve deployed them on another project, so we've built that experience level. So I think, obviously, the ability to tap into that information quickly, because a lot of it has to do with speed to market and how quickly are you able to access the talent and fill the client's needs.

Brian Manning: As you know, every year we run the Small Business Credit Survey which tracks economic conditions, financing needs, and credit availability for small businesses. How did you finance Artech’s growth? What sources of funding did you look to?”

Ranjini Poddar: Early on it was really about getting some initial funding from friends and family, and that helped us get through the first year or two. And then it's really been all financed from either the profits of the company or bank financing. So we've been fortunate—I think we've been prudent in terms of how we've invested and getting the right type of financing at the right time and have had very strong relationships with our banking partners who have really supported us through our growth.

Brian Manning: So, you've been in business since 1992, or thereabouts?

Ranjini Poddar: Yes.

Brian Manning: Can you tell me about some early challenges you may have faced and what you might have learned from them, or learned as the business was growing?

Ranjini Poddar: I think the first is, of course, developing a strong customer base, or really any customer base. I think my advice to folks that are thinking of starting their own business is to really define what you want to do or what's the service you want to provide or the product you want to sell. I think a mistake that many entrepreneurs make is you're hungry for business, and because you're hungry for business, you think any business is fine. And so you try to sell yourself as being able to do anything and everything, and prospects see right through that because they know that you're a small firm and you cannot do anything and everything. And I think that also hurts you because you're not able to articulate a value proposition to your prospects, and it's more difficult to land clients.

So my first advice would really to be very clear and really turn away—it doesn't even come to turning away but articulate to your prospects, “No, this is something we don't do. This is our sweet spot. This is what we do, but this is what we're not good at. And I don't think I could in good stead tell you that we can provide a good product or service in that area.” And we are much larger, so our scope of services are much broader, but I still do that today, when a client comes to us and says, “Well, can you help us with this?” And it could be in a geography. For example, recently a client came and said, “Can you support us in Latin America?” And we said, “Look, these are the geographies that we have operations in. We'd love to be able to support you there, but we don't have operations, and we wouldn't be a right fit for you,” because you can get spread too thin and not be able to execute well.

Brian Manning: Well, this actually provides a nice segue into my next question which is, over the years, you've expanded into new states and now into new countries. How do you decide when to enter a new market?

Ranjini Poddar: We work nationally across the U.S. We have employees in about 40 plus, 40 to 45 states at any given time, but we have client-facing locations in about 15 to 20. It varies. And our decision in terms of expanding in the U.S. is really built on client relationships. So if we have, for example, about three years ago we signed a contract with a major bank that had operations in six major markets in the U.S. And at that time we were really only active in one or two of those markets. So as a result of that contract with the bank, we ended up expanding our operations to all six of those markets, because we saw the opportunity, we knew if we built our internal team and operation, we would be able to drive revenue. So in the U.S., we really use that as a method of sort of a cornerstone account or two to decide, okay, you know, I'm going to do business in this particular market. And then once we land that account then we expand around it.

Brian Manning: As Artech has expanded over the years, what challenges have you faced? For example, did you have any particular difficulties during the financial crisis?

Ranjini Poddar: You know, we were actually very fortunate for a very odd reason. At that time, we were not very exposed to banking and financial services in terms of our client base, and we were highly focused in terms of system integrators and technology firms. And they, of course, felt the secondary impact, but they didn't have the primary impact of the financial crisis. So we actually ended up growing through those years and actually didn't feel much impact at all. Today, we are much more exposed to banking and financial services. I think three to four of our top 10 accounts are banks now, so if something similar was to happen today, we'd have to manage through it much differently. But over the last 26 years now, we've managed the firm through a few downturns. The dot com—well, we started out during a recession and have gone through, have managed through— and continue to grow and be profitable through—two or three downturns. So I think we're prudent in terms of our management practices.

Brian Manning: Okay. So, the company has grown a lot over the years. Was it organic? Were you out there making acquisitions?

Ranjini Poddar: Most of our growth has actually come organically. You know, there was a period of time where we had double-digit, year-over-year growth. That's obviously much harder to attain when you're a much larger firm, but we have done three acquisitions along the way. They have all been, you know, relatively small acquisitions relative to our size, about $20 million in revenue, plus-minus, for each one. And we did the first one in 2011, then ’14, and then ’17. And it was really around geographic markets that we felt that we found a great firm that was a strong fit culturally with Artech and had a client base that was not significantly overlapping. So we were trying to fill a geographical gap as well as acquire clients, and, of course, the internal team. And that's been a great educational experience, or development experience. For me personally, I've learned a lot through doing those acquisitions, and I think it's definitely contributed to our growth and our capabilities.

Brian Manning: What have you learned? What will be some of the key lessons from doing acquisitions?

Ranjini Poddar: I think first and foremost is really about culture. You know, I think we didn't realize how significant that was before we did our first acquisition. And I think that was—I think all three have been successful in terms of that they have all been additive to our business. And I wouldn't say that any of the three that we've done have been unsuccessful. However, I feel the last one we did has been the most successful because we were really able to identify the cultural fit, learning through having done others and learning the mistakes. So it's, I mean, everyone says this, that it's all about the culture.

Brian Manning: Tell me about your experience being the head of a minority and woman-owned business, and how does that affect how you run the business and how you manage the business?

Ranjini Poddar: It's obviously a lens through which I live my life and manage Artech. Many of our clients actually have programs that support diversity in their supply chain, and many have been very helpful in terms of our growth, in terms of supporting us through our growth, and helping us grow our capabilities and driving business. Internally, I think, we have a different feel because we have a very diverse team internally. There are folks from all types of backgrounds and religions and perspectives, and I think, frankly, that makes us a lot better because some of our competitors are perhaps, sort of have grown up a certain way and only have one viewpoint, whereas I think we have very divergent viewpoints. So I think we often come to a solution—I guess a solution would be the right word—a solution for a client that may be, you know, that’s the result of five different types of input as opposed to five different people saying the same thing.

Brian Manning: What is your outlook for the business over the next few years? Do you see any particular opportunities or challenges?

Ranjini Poddar: So our industry typically tends to be a leading economic indicator, and I think I've been waiting for the other shoe to drop now for quite a while. And so far, knock on wood, it hasn't. It just seems to be chugging along, and the demand seems to be endless. And the only constraint is the supply of talent. So yeah, I mean I think it's the crystal ball that I don't know that anyone can answer, which is when will the economy turn? Right? But even when it turns, I mean, IT has become so integral to any business that while our clients will of course cut back on their investments, they still need to maintain and they still need to make investments. So it's just a matter of magnitude.

Brian Manning: What advice do you have for current and aspiring small-business owners, and would you do anything differently knowing what you know now?

Ranjini Poddar: Oh, there's probably a list of 1,000 things that I would do differently, if I knew what I know now, 26 years ago. But coming back to the first part of your question, my advice would really be around, you know, I think I'm a little bit of a different type of entrepreneur in the sense that I don't have any big, wonderful ideas. I'm not going to invent the next Tesla or whatever the next gadget is, but what I am good at is executing on a plan, creating a plan and executing on it. And I think a lot of entrepreneurs, they have ideas but they don't focus on the execution. And ultimately you can have all the ideas in the world, but if you're not able to execute on it, then you're not going to make money, and if you're not going to make money, then you're going to go out of business. So, I would really give the advice to any new business startups is to really create your plan. And it doesn't need to be set in stone. I mean, you're always adjusting it and modifying it based on market conditions, based on what you're learning, based on where you are finding success. But really at least create a plan and focus on executing it.

Brian Manning: So, Ranjini, thank you very much for joining me today. It's been a pleasure speaking with you.

Ranjini Poddar: I had a great time. Thank you for all the wonderful questions, and I hope the audience finds some of my advice useful.

Javier Silva: Welcome to Bank Notes, a podcast by the New York Fed. For this inaugural series, we’re discussing Small Business. I’m your host, Javier Silva.

In this series we’ll share insights and analysis from the New York Fed on a range of small business issues, including credit needs and challenges. We’ll also hear from small business owners about their experiences: the highs, the lows and everything in between. Before continuing, I would like to note that the views expressed in this podcast do not represent those of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the United States produced more than 215 billion pounds of milk in 2017. Today, we’re going to introduce you to someone who is on the front lines of that production. No, he’s not a farmer. He’s Kevin Ellis, the CEO of Cayuga Milk Industries, a small business that processes milk from 30 family-owned dairy farms in the Finger Lakes region in New York. The company ships it to places near and far, even as far away as Kuwait. Today we’ll learn about Cayuga Milk Industries—how it got started and why this small business is making an impact on the dairy market.

Javier Silva: How did you get into this business? How did you become the CEO of Cayuga Milk industries?

Kevin Ellis: I grew up on a dairy farm in upstate New York, just south of Syracuse.

And I went to Cornell University in animal science, where I wanted to be a vet, but I ended up having a keen interest in business, and I came out and got into finance. And I first started financing farms and got into business consulting, and it was during that time of doing business consulting where I met many of the current members of Cayuga Marketing and the investors in Cayuga Milk Ingredients. So, I had gotten into finance in Rochester, New York, in doing commercial real-estate finance, and I got a call from one of the farmers that is currently a member of Cayuga Milk Ingredients, wanting to know if I would entertain coming to work for them in developing a value-added milk-processing venture.

Javier Silva: Tell us a little bit about Cayuga Milk industries. What is it?

Kevin Ellis: Who we are is a group of 30 farmers who came together as Cayuga Marketing to sell their liquid milk from the farms directly to manufacturers throughout the Northeast. Cayuga Marketing created Cayuga Milk Ingredients, which was invested in to be a market for their milk. So today we manufacture high-grade, high-quality dairy ingredients from that raw milk from those farms, in addition to selling that milk around the northeast area to other manufacturers.

Javier Silva: Oh, interesting. So, how does that work? What are you pulling apart?

Kevin Ellis: So milk in its basic form is fat, it's protein, and then it’s other solids such as lactose. So when we bring it into our plant, we separate the cream off it, and we sell the cream off to further processors for half-and-half and heavy whipping cream and ice cream, and we also have a customer that makes cream cheese with the fat portion. And then what's left is the skim milk. We take the skim milk, and we harvest the proteins out of that, and we can either sell them in liquid form or we can dry them and sell them in a dry powder form that's used in the sports-nutrition industry, it's in clinical nutrition, and then also in further food processing like cheese manufacturing. And then we also manufacture high-grade skim milk powder that's used to make other milk products in countries that don't have dairy cows, such as one of our customers in Kuwait takes the milk and reconstitute it for fluid drinking milk.

Javier Silva: What was the size of the company when you started at Cayuga?

Kevin Ellis: Well, when I started at Cayuga, I was employee one, and now we have 72 employees, and we basically grew it from nothing into what it is today. We were actually, it was a collective group of farms that were marketing their milk through another organization, so really didn't have sales per se. It was more of a negotiation as a collective bargaining group, more or less. You know, our annual budget was maybe $300,000, $400,000. It wasn’t a big enterprise. So, when I came my initiative was to build a value-added processing plant. So I worked on that for a few years, and then when we finally launched, the company that we were selling our raw fluid milk with basically asked us to leave. So we ended up creating two companies. So we had to figure out how to also market all of our milk as well as process the milk. That wasn't always our original plan. So the one company had to be created in about three and a half months, so it took some effort. And today we’re probably better off for it, but it was pretty stressful at the time.

Javier Silva: One of the aspects that we focus on at the New York Fed through our Small Business Credit Survey is how business owners access the financing that is essential to starting or growing their businesses. Can you share with us how you got financing to start and grow Cayuga?

Kevin Ellis: Well, luckily, we finance today with a company I used to work for, so I knew their capabilities, I knew how they operated, but frankly when we took over operations, we had $350,000 in the checking account, so we had to figure out, first, how to pay the farmers. I think the first farmer payroll was near $8 million, so we had to get creative in a hurry. And we convinced our lender to work with us on a borrowing base because, not only did they finance the company, but they financed the farms, so they knew it was in their best interest to find a workable solution. When we financed the company, the manufacturing plant—it was $104 million investment, and we used traditional bank financing to put that together, but we really didn't have any equity. We have some strong farms in the group, and they were able to leverage their farm assets to be able to put money into the new venture, and we capitalized that to about 45% equity, and then the rest came in as syndicate debt. So, we have five participants in our syndication on that side of it. It was a lengthy process of, I call it creative finance, a lot of what we did.

Javier Silva: So for our listeners that may not be familiar with syndication, what does that mean exactly, you have five syndicators?

Kevin Ellis: Syndication is a group of bankers that work together because none of them want to take all the risk themselves. So it's a way to spread risk. And typically you'll have a lead bank, and the lead bank will then syndicate it out. And what that means is they partner. They'll sell pieces of the loan to other parties to decrease their risk.

Javier Silva: Did you apply for any grants or other types of funding from either New York State or other entities?

Kevin Ellis: We did. I applied for every grant that I could possibly think of. And at the end of the project, we were awarded just over $5 million dollars in grants from the state. And I did apply for one USDA grant, which that's the only one we didn't receive, actually. So all of the money came from New York State.

Javier Silva: Were there any financing options you didn’t pursue?

Kevin Ellis: We did consider, but didn't go down the path of VC or angel financing. I had enough knowledge of that industry where I knew the kinds of returns that they were expecting weren't the kind of returns that agriculture typically can throw off. We want to find strategic partners because more or less farmers think generational. They don't think short term. They think about making an enterprise for the next generation. So we knew that type of funding wouldn't fit our mantra.

Javier Silva: That makes sense in terms of thinking over to several next generations to keep that farm going within the family. It's more important than other factors, I imagine. Since the collective is really a group of small businesses, how do you work with these farmers to help them succeed—because if they succeed, you succeed. So how do you work with them to help them be more efficient with what they're doing?

Kevin Ellis: Well, honestly, we look at all different avenues to assist them, whether it's through bulk purchasing. We've just gone through an exercise where we've looked at buying supplies in bulk, that all the farms can take advantage of bulk purchasing versus purchasing by themselves. We have a full-time staff person that works with the farms, and we do that because it's more economical to have one staff person that works for us than each farm finding 30 different ways of dealing with the same issue. And she works for the farms on OSHA compliance and some other endeavors and translation services and those types of things. We're also in the early stages of looking at a captive where we could all share in a risk profile to get insurance possibly a lot cheaper, and just working together to make sure that we're always trying to benefit each other. But I don't want lose sight of my primary job and the primary job of Cayuga Milk Ingredients is to provide a profit back to the farms, which will increase their sustainability long term.

Javier Silva: Can you tell us how your relationship with the farmers has evolved over time? Thinking back to when the company started, what’s different today?

Kevin Ellis: One of the reasons that farmers or this strategic group of people would build a processing plant is because they want to understand and be closer to the markets that they're serving. And when we first started up my farmers were milk producers. They didn't have a lot of market insight. They didn't get a lot of feedback from the marketplace. And I think one of the things that's changed over time and I've been very transparent with my investor group about is what is happening in the market. Good, bad, or indifferent. We are very transparent, and we watch the trends, and I try to bring back opportunities in real time so we can move quickly. And one of the great things about my farmer group is they’re very creative and open minded, and they move quickly. So when they see an opportunity, they'll seize it. So that's one of the things that we've been able to do with our new company is that I'll come back and I’ll say, There’s a trend here with non-GMO, and there’s interest in non-GMO, and they'll do it. At the end of the day, if there's more benefits than there are negatives, we'll do it. So it has, the discussions in the boardroom have changed quite, quite a lot in the last 10 years.

Javier Silva: So it sounds like you're serving demand and serving the market rather than producing, if you kind of think of it that way, thinking about how do we serve the market?

Kevin Ellis: It starts with me. I'm a 100% market-based, and it's trickling down to the farm now, where they know—and I hear them discuss it now, where I know—they talk about well we're here to serve a market; we're not here to produce products. It's changed their mentality.

Javier Silva: Let’s talk about your workforce. You know, you're located in an area that’s not as dense as other regions, especially particularly downstate. So how do you go about attracting talent to Cayuga Milk and keeping talent, especially for more specialized positions?